Ted Kennedy had been entrusted with overseeing 13 western states for his brother's 1960 presidential campaign. It was a tough assignment, since many of the states were Republican strongholds. In the end, he failed to deliver all but three of them.

"Can I come back," the youngest and breeziest Kennedy wired his rabidly competitive family in a post-election telegram, "if I promise to carry the Western States in 1964?"

The move — using his fun-loving personality to paper over his failings — was classic Teddy. Even though he had grown into a handsome 28-year-old man with angular features, he was still largely seen by his high-achieving siblings as the overweight baby brother who was great for a laugh or a hug, but nothing of consequence.

Yet his telegram also masked a surprise: Ted Kennedy didn't really want to come home.

If a lifetime of unfavorable comparisons with his older brothers was only going to intensify now that one was about to become president and the other attorney general,

Ted figured he'd have a better shot at being his own man if he left the compound.

He wanted to move with his new wife, Joan, to one of those western states he'd explored during the campaign — New Mexico, California, or Wyoming — and maybe buy up a newspaper and eventually run for office. "The disadvantage of my position," he once told an interviewer, "is being constantly compared with two brothers of such superior ability."

But his father shot down his wild west dream, deciding Ted would be crazy to throw his hat in any ring outside Massachusetts. No, he would run for the US Senate seat his brother Jack had vacated to become president. "We really wanted to go out West," Joan Kennedy recalls, "but in those days, my late father-in-law said, 'You do this,' and you did that."

Ted did not resist, embracing the opportunity to justify the patriarch's faith in him. But his brothers Jack and Bobby, and especially their advisers, strongly opposed a run by Teddy.

They thought he wasn't ready — it would be another two years before he even reached the minimum age for senators set by the Constitution. And they feared that, win or lose, his bid would reflect poorly on the new president.

Undeterred, the patriarch put the wheels in motion. Ted took a job as an assistant district attorney in Suffolk County and, after hours, was ushered around the state to speak before every Kiwanis Club, PTO, and temple brotherhood that would lend him a microphone. President Kennedy agreed to leave his kid brother's options open. He saw to it that his old college roommate, a non-threatening former Gloucester mayor named Ben Smith, was appointed to warm the Senate seat until an election could be held in 1962, the year Ted reached the required age of 30.

In time, Jack accepted the inevitability of his brother's run. Adviser Ted Sorensen says JFK decided he was already opposing his father on too many fronts, and, on family matters at least, even the president answered to a higher authority. Yet Bobby remained skeptical.

In the summer of 1961, Ted wrote to inform his father that Edward McCormack, the popular Massachusetts attorney general and a certain candidate for the Senate, had told a mutual friend he doubted Ted was going to run for the seat. That's because at a luncheon in Washington, Bobby had publicly showered McCormack with praise. "When I heard this, I ran down brother Bob and he said, 'What's so bad about that?' — he would say some nice things about me, too," Ted wrote. "So you can see what I am up against here, Dad."

A few days before Christmas of 1961, Joe Kennedy Sr. fainted on the golf course next to his Palm Beach estate. It was a massive stroke. Ted rushed from Boston, bringing a vascular specialist with him. His brothers came as well, but Ted stayed at his father's bedside for three straight nights. When it became clear the patriarch would survive, but in an incapacitated state, robbed of much of his mobility and ability to speak, the news was crushing to his children. As demanding as their father had been with them — Ted once compared him to a blowtorch — and as unscrupulous as he had been in some other facets of his life, for his children he had been both a rainmaker and a source of incredible love. That was especially true for Teddy, who, like many youngest children, had an easier relationship with his parents than his older siblings. Now he had lost the benefit of his father's sure hand just when he needed it most.

Many people expected Ted to drop his Senate plans. The Kennedy advisers in Washington certainly hoped he would. They especially dreaded a bruising battle with McCormack, who was the favorite nephew of the US speaker of the house, a leader whose support JFK needed to get his agenda through Congress.

Yet inexperienced, undistinguished, untested Teddy Kennedy chose to soldier on. Instead of making a name for himself in a new state, he would cut his political teeth running for his brother's old seat, working out of his brother's old Beacon Hill

apartment, and seeking to reflect in his brother's glow with the winking campaign slogan of "He Can Do More for Massachusetts."

Iconic career begins haltingly, skittishly After Ted Kennedy formally announced his candidacy in March of 1962, Harvard Law School professor Mark De Wolfe Howe spoke for many intellectuals when he called the youngest Kennedy "a fledgling in everything except ambition." The rejection by liberal academics was troubling for two reasons. Many of them had been enthusiastic supporters of Jack's, and many of them knew Teddy's secret.

Chatter about how Ted had been kicked out of Harvard for cheating — proof in many minds of his inferior ability — finally forced JFK to intercede. The president summoned the Globe's top political writer, Robert Healy, to the White House, where he negotiated how the cheating news would be released. Healy insisted it go on page one, but he and his bosses agreed to blunt the impact, using the softball headline of "Ted Kennedy Tells About Harvard Examination Incident," and delaying any mention of the actual transgression until the fifth paragraph.

Liberals favored Eddie McCormack largely because of his civil rights record, which was surprisingly progressive considering he was the son of South Boston neighborhood powerbroker Edward "Knocko" McCormack. Knocko kept a chalkboard in his Southie bar listing the names of people he had personally banished, at times using ethnic slurs to describe the reason for their banishment, such as "Brought a Guinea to the bar."

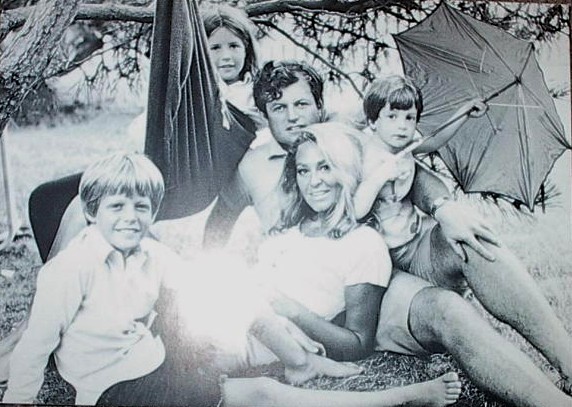

With most seasoned pols staying on the sidelines, Ted came to rely heavily on Gerard Doherty, a young state lawmaker from Charlestown. Ted found another effective advocate closer to home: his wife. "Let's show them, Joansie," he told her.

Innocent and so wholesomely pretty that Jack nicknamed her "The Dish," Joan had simply not been prepared for the hard-driving Kennedy culture. Her naivete in revealing to journalists Kennedy secrets such as Jackie's reliance on wigs and Jack's inability to lift his children because of his bad back had lowered her standing in the family.

Yet Doherty, who was hoping to see Ted outgrow his initial stiffness on the trail, noticed how quickly voters warmed up to unpretentious Joan, and Joan relished the chance to be in common cause with her husband, having been apart from him for long periods of their short marriage. "It was just us kids," Joan says now. "And it was one of the happiest years of my life."

In the spring, Doherty was called to the White House for a meeting with the president and his advisers, many of whom were still refusing to return the campaign's phone calls. As the president stood up to leave, he turned to his advisers and said, "I want everyone to know that it's very important to me — and to everybody in this room — that my brother does well." The next day Bobby reaffirmed the message.

While Jack and Bobby continued to keep their distance in public, that was the turning point. The

Kennedy machinery now kicked into high gear to support Teddy, helping him win the endorsement of the state convention in June.

McCormack thought he could still beat Kennedy in the September primary, but by the summer Ted had developed into a confident campaigner, reaching down manholes and climbing up telephone poles to shake the hands of workmen. As a boy, Teddy had learned at the knee of his back-slapping, central-casting-of-a-pol grandfather John "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald. Now he put those lessons to use.

At the first debate, which took place in South Boston, McCormack came out swinging. His hope, according to campaign manager Sumner Kaplan, was that "Teddy wouldn't be able to take the pressure and he might blow up."

McCormack ridiculed Kennedy for his lack of qualifications. "The office of United States senator should be merited, and not inherited," the speaker of the house's nephew thundered.

Kennedy, shaky at times, stuck to his rehearsed answers and resisted McCormack's bait. His voice cracking, he said in closing, "We should not have any talk about

personalities or families."

But that just fired up McCormack more. Jabbing his finger in the air toward Kennedy, McCormack scoffed that if his opponent's name were Edward Moore, his candidacy "would be a joke." Over wild applause, he continued, "But nobody's laughing because his name is not Edward Moore. It's Edward Moore Kennedy."

Veins bulging, Kennedy managed to contain his rage. When the debate ended, he walked off the stage without shaking McCormack's hand. To Doherty, he muttered, "I'd like to get that guy and punch him in the nose!"

Fortunately for Kennedy, he wasn't the only one fuming.

When Kaplan walked into the crowd to chat with his own mother, she blasted him for being party to a bludgeoning and refused to talk to him for weeks.

On the drive home, Kaplan and McCormack listened to the radio as caller after caller — many of them older women —

expressed the same indignation with McCormack's behavior that Kaplan's mother had.

"Turn it off," McCormack said finally. "The race is over."

Kennedy beat McCormack by more than two-to-one. In the general election, he faced yet another political scion, Republican George Lodge, whose great-grandfather had defeated Honey Fitz for the Senate and whose father had lost the same seat to JFK. Ted cruised to victory.

'He's dead,' Bobby tells his brother In November 1963, Ted was presiding over the Senate, a thankless clerical job assigned to junior members, when a press aide ran in. "The most horrible thing has happened!" he said, "It's terrible, terrible!"

"What is it?" Kennedy asked.

"Your brother. Your brother the president. He's been shot."

Ted had been in the Senate for less than a year, but his reception had gone better than expected. Those hidebound leaders of the ultimate old man's club had expected a swagger of entitlement from the president's kid brother. But Ted turned out to be the model of deference, charming his elders with warmth and humor. Growing up the youngest of nine had prepared him well for an institution that runs on seniority. And while he never flaunted his status as brother of the president, he had taken to the arrangement. Jack thoroughly enjoyed his company, inviting him often to the White House for some after-hours laughs.

In one hideous moment, everything had been

thrown into doubt.

The next several hours were a blur and an eternity as Ted sped in his aide Milton Gwirtzman's black Mercedes from the Capitol to his home in Georgetown, determined to make sure his family was safe and struggling to find a live line in Washington, where much of the telephone system had gone down, and get a hold of Bobby. Bobby would know what to do. He finally reached his brother.

"He's dead," Bobby said plainly, according to William Manchester's book "Death of a President." "You'd better call your mother."

Ted flew to Hyannis Port to deliver the shattering news to his ailing father. Soon after the funeral, the family reconvened at the compound for Thanksgiving. One night that weekend, Ted stayed up all night, drinking and swapping ribald stories with friends about the good times with Jack.

The next morning, his children's governess quit in a huff, telling Joe Kennedy's nurse, Rita Dallas, how horrified she'd been by Ted's behavior. Dallas says the woman clearly didn't get the concept of an Irish wake.

It was more than that. A man who had spent most of his life drawing laughs in his role as the baby brother must have known that, on some level, the laughter had just ended for good.

So much more would be expected of him now.

Plane crash incapacitates, his recovery fortifies On April 9, 1964, Ted Kennedy rose to deliver his first major speech in the Senate, in support of the Civil Rights Act. President Kennedy had proposed the legislation the previous spring, and now it had come up for debate. "My brother was the first president of the United States to state publicly that segregation was morally wrong," Kennedy told his colleagues. "His heart and his soul are in this bill."

Two months and much filibustering later, the Senate was poised on June 19 to pass the historic ban on racial discrimination. Kennedy expected the vote to happen by early afternoon, after which he would fly to Springfield, where he would be formally endorsed by the Massachusetts Democratic Party for his first full term as senator. He had asked his friend and fellow senator, Birch Bayh, to come with him and deliver the keynote address.

But debate dragged on. The bill didn't pass until 7:40 p.m. Joan was already in Springfield. Ted boarded a twin-engine private plane along with Bayh and his wife, Marvella, as well as Ed Moss, Ted's aide who had developed into a close friend. Moss sat in the copilot's seat, Ted and the Bayhs in the back.

It was a turbulent ride, with stormy weather and very little visibility. At 10:50 p.m., the plane crashed in an apple orchard outside of Springfield. Bayh crawled out a window, then helped his wife get out.

He screamed for Ted, but got no reaction. It was too dark and foggy to see in the cabin. He walked around to the front of the plane, and peered in. Both the pilot and Ed Moss appeared to be dead. He and Marvella starting running for help. But worried the plane might go up in flames, Bayh went back and dragged Ted out. He had regained consciousness but could not move his legs.

When news reached the convention hall, Joan was whisked to the hospital to see Ted, who had arrived badly injured and in shock. The convention was abruptly disbanded. The pilot was dead at the scene, but Ed Moss was still clinging to life. The father of three young girls, he survived for a few hours more, long enough for his wife to see him unconscious.

As soon as Bayh arrived at the hospital, he phoned Bobby, telling him there'd been a terrible accident.

"He isn't dead, is he?" Bobby asked.

"No, we've been told by the doctor that he has a serious back injury."

At the hospital, a reporter asked Bobby, "Is it ever going to end for you people?" Somberly, he responded,

"I was just thinking out there if my mother hadn't had any more children after her first four she would have nothing now. . . . I guess the only reason we've survived is that . . . there are more of us than there is trouble."

Doctors initially feared a spinal cord injury, but the damage was limited to three fractured vertebrae in his lower back, a collapsed lung, and two fractured ribs. It would be a long time before he would walk again. After a few weeks, he was moved to New England Baptist Hospital in Boston. When doctors recommended Ted undergo lumbar fusion surgery, his father, who had visited the hospital with Rita Dallas, strenuously objected with what little speaking ability he had, "Naaaaaa!" Jack had nearly died as a result of complications from his spinal fusion surgery. Joe Sr. wasn't going to take that chance again. "Dad," Ted told him, "you've never been wrong yet, so I'll do it your way."

Ted was confined for months in a Stryker frame bed, which allowed him to be kept completely flat but flipped around to change positions. The arrangement complicated his reelection bid, but it provided another opportunity for Joan to prove her usefulness. She gamely filled in for her husband at campaign events, delivering cute stories and updates on his condition before reading the text of his speeches.

Unexpectedly, there was a major upside to Ted's long convalescence. Respected academics began coming in weekly to give him bedside tutorials across a range of topics. Even his blistering critic from the 1962 campaign, Mark De Wolfe Howe, who gave him a primer on civil rights law, had to admit that the kid had learned a lot.

Through these months, a new seriousness developed in Kennedy. Jack had been cut down in his prime, joining their older siblings in an early grave. He himself had barely escaped death in a crash that had killed two others. Life was too precious to waste coasting and clowning around.

During one bedside talk with Gerard Doherty, his manager from the '62 campaign, Kennedy asked how his firefighter father had survived financially when Doherty endured a long battle with tuberculosis during college. Doherty detected in him a growing appreciation for the economics of healthcare, an appreciation that would become Kennedy's cause of a lifetime: If medical crises test even wealthy people such as the Kennedys, how do ordinary people cope?

On election day, Kennedy walloped his Republican opponent. Bobby, who had hastily run for a Senate seat from New York, also won, though by a much slimmer margin.

At a joint news conference outside the hospital, Ted ribbed his brother about the narrowness of his victory. Bobby quipped, "He's getting awful fresh since he's been in bed and his wife won the campaign for him."

A photographer told Bobby, "Step back a little, you're casting a shadow on Ted." Teddy shot back, "It'll be the same in Washington."

Finding his stride in Senate spotlight Ted needed the support of a cane as he walked back into the Senate in January 1965, but in all other respects, he showed a vigor his colleagues had not seen before. Deference had served him well, but now he was determined to get things done. He brought on a new senior aide,

David Burke — a sharp guy with an MBA from the University of Chicago and the tough son of a Brookline cop — and gave him the mandate of attracting the best Ivy League talent to remake his staff.

Bobby's arrival in the Senate presented complications. Although Ted outranked his brother in seniority, Bobby was a national figure determined to use his Senate office as a formidable check on Lyndon Johnson's power.

On visits with his father at the compound, Ted would joke, "I was OK in the Senate until Bobby came in and upset everything." In reality, they managed to develop a good working relationship.

In 1965, voting rights became the big issue. Civil rights leaders lobbied the Kennedy brothers to push for an amendment to the Voting Rights Act to remove the poll tax, a noxiously effective tool used to deny blacks the right to vote. But the Johnson administration opposed the amendment, worrying it might endanger the rest of the act.

From his perch on the Judiciary Committee, Ted Kennedy took on both a popular liberal president and entrenched conservative senators in his effort to end the poll tax. He lost, but the vote — 49-45 — was much closer than anyone expected and won Ted wide praise outside the Senate and a new standing within it. That same year, he scored another victory in pushing through reform of the nation's outdated immigration laws, which greatly favored people coming from Northern Europe.

On the heels of this success, Kennedy blundered by pushing for the appointment of Francis X. Morrissey to the federal bench. He did it out of loyalty to his father, for whom Morrissey had been a retainer and supplicant.

LBJ agreed to nominate the unqualified Morrissey but was most likely setting the Kennedys up for a fall. That came soon enough.

Healy, the Globe writer who had gingerly broken the news of Ted's expulsion from Harvard, uncovered material that formed a withering indictment of Morrissey's lack of readiness. The Globe was handed the Pulitzer Prize for its coverage, and Ted was handed an embarrassing defeat.

There were other struggles during this period, especially on the home front. In the six years prior to delivering their third child in 1967, Joan had suffered three miscarriages. And by the middle of the decade, she says now, she learned of Ted's extramarital affairs. She didn't know what to do, so she turned to Jackie Kennedy.

The two sisters-in-law had long enjoyed a warm relationship. When Bobby's wife, Ethel, and the Kennedy sisters were playing touch football with the men at the compound, Jackie and Joan would steal away,

Jackie painting and reading, Joan playing her classical piano. The Kennedys had trouble understanding why someone would opt for alone time and artsy pursuits when there was so much fun to be had competing with the clan.

"They think we're weird," Jackie had once told Joan. Now Joan turned to Jackie for advice on handling a cheating husband. "He adores you," Jackie told Joan, adding, "The whole family loves you, and you're just the perfect wife, but he just has this addiction."

Joan believed her. But as a vulnerable soul, and the daughter of an alcoholic, she eventually would find support in a bottle.

And the distance between her and Ted would grow.Ted himself drank quite freely during this period, but because he was developing an ability to compartmentalize his life, it didn't seem to affect his work. Every night he'd pore over the materials his aides had stuffed into his bulging briefcase — "the bag" — earlier in the day.

He quickly rebounded from the Morrissey debacle and pushed through lasting legislation, including the creation of a National Teacher Corps and a system of community health centers. In 1967, he adroitly led the fight against a redistricting measure that had powerful backers and would have hollowed out the concept of "one man, one vote."

As with the poll tax, Ted had taken the lead on redistricting and Bobby had played a supporting role. It was an arrangement that would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier but which now spoke to the manner in which Ted had emerged as a force. It also spoke to the closeness with which he and Bobby were now operating. There was still considerable rivalry, but it was mostly expressed through humor. During a string of speeches on the West Coast, Bobby joked about the telegram he had received from Washington. "Lyndon is in Manila. Hubert [Humphrey] is out campaigning. Congress has gone home. Have seized power. Teddy."

In his own speeches, Ted would recount Bobby's joke and then add, "Everyone here knows that if I ever did seize power the last person I'd notify is my brother."

One Kennedy decides to run, a second says no Everyone, it seemed, around Bobby wanted him to run. Everyone except his brother. Ted used cold political terms to frame his opposition to a 1968 presidential bid by Bobby: It would be nearly impossible to defeat a sitting president, even one as weakened by the Vietnam War as LBJ. And just by trying, Bobby would divide the party, ensure the election of a Republican, and perhaps cost himself the chance for the presidency in 1972. Reluctantly, Bobby agreed.

Then on March 12, antiwar candidate Eugene McCarthy stunned LBJ and the political world by pulling down

42 percent of the New Hampshire primary vote. Four days later, Bobby announced he was in.

Ted now threw everything he had into getting his brother elected. He headed west to line up support from big-city mayors and labor leaders and dispatched Doherty to run Bobby's campaign in Indiana, the first primary in which he hoped to compete. The fact that Doherty, who knew little about Indiana, would be running so critical a state for Bobby was an indication of how rushed and improvised the whole operation was.

Two weeks later, Ted was dining with Doherty at an Indianapolis hotel when they watched Lyndon Johnson shock the nation with his announcement that he wouldn't run for reelection. After Bobby won the Indiana primary, the focus shifted to the biggest prize: California.

On the night of June 4, Ted delivered a speech in San Francisco, thanking Bobby's Northern California workers. Returning to their suite at The Fairmont hotel, he and Dave Burke flicked on the television to watch Bobby deliver his victory speech from Los Angeles.

"Be quiet, be quiet!" someone was yelling on the TV, straining to rise above the pandemonium. "Everyone be quiet!"

"What the hell's going on?" Ted asked Burke.

"I don't know," Burke replied, trying to suppress his panic.

"We'd better go there."

Hearing that Bobby had been shot, Burke rushed out of the room and sprinted down 12 flights of stairs to the lobby, where he arranged a flight to LA.

The whole flight, gregarious, backslapping Teddy barely said a word.

The next day, after it was clear Bobby could not be saved, his spokesman Frank Mankiewicz was walking out of Bobby's hospital room when he spied a figure standing in the adjoining, dimly lit bathroom. It was Ted. "I have never, ever, nor do I expect ever, to see a face more in grief," Mankiewicz recalls.

Ted spent much of the night before Bobby's funeral driving around New York with his close college friend and former aide, John Culver, who was now a congressman. By now, Culver knew that as garrulous as Ted could be in happy times, in grief he turned inward and quiet.

Ted stayed strong as he delivered the eulogy to his brother, his voice cracking only near the end.

"Those of us who loved him and who take him to his rest today," he said, "pray that what he was to us and what he wished for others will someday come to pass for all the world."

The whole world was watching, but Ted was all alone. Jack's assassination had left him devastated, but at least Bobby had been there to be his rock. Bobby's assassination removed the final buffer. Ted now felt the obligation to lead the sprawling family, especially Bobby's, which was still growing, since Ethel was pregnant with their 11th child.

Much more would be asked of him.

Going into the Democratic National Convention in Chicago just two months later, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley and other powerbrokers pushed Ted to agree to be drafted as the presidential nominee. They decided the divided Democrats were doomed to lose the presidency under presumptive nominee Hubert Humphrey. Only a Kennedy could unite them.

Eventually, Kennedy instructed Culver to deliver a letter to the convention chairman stating his refusal to accept the nomination. Culver says Kennedy knew that even if he were able to win, it would only be as a stand-in for his brothers. If Kennedy delayed in quashing the draft movement, Culver says, it had less to do with genuine interest in the job than with his sense of duty to keep the country together, to end the war that was tearing it apart, and to honor his brothers by carrying out their agendas.

In his six years as a senator, Ted had found his place. After a lifetime of coming up short in comparisons to his brothers, he had already proved himself to be a more effective legislator than either Jack or Bobby. If he could honor their legacies without changing offices, Culver says, that would have been his preference.

Besides, no one could have foreseen how his presidential prospects would forever be changed just one year later. "He felt understandably that he was 36 years old," Culver says, "and that ring would come around again."