July 18, 2009In 1964, I was flying with several companions to the Massachusetts Democratic Convention when our small plane crashed and burned short of the runway. My friend and colleague in the Senate, Birch Bayh, risked his life to pull me from the wreckage. Our pilot, Edwin Zimny, and my administrative assistant, Ed Moss, didn't survive. With crushed vertebrae, broken ribs, and a collapsed lung, I spent months in New England Baptist Hospital in Boston. To prevent paralysis, I was strapped into a special bed that immobilizes a patient between two canvas slings. Nurses would regularly turn me over so my lungs didn't fill with fluid. I knew the care was expensive, but I didn't have to worry about that. I needed the care and I got it.

Now I face another medical challenge. Last year, I was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. Surgeons at Duke University Medical Center removed part of the tumor, and I had proton-beam radiation at Massachusetts General Hospital. I've undergone many rounds of chemotherapy and continue to receive treatment. Again, I have enjoyed the best medical care money (and a good insurance policy) can buy.

But quality care shouldn't depend on your financial resources, or the type of job you have, or the medical condition you face. Every American should be able to get the same treatment that U.S. senators are entitled to.

This is the cause of my life. It is a key reason that I defied my illness last summer to speak at the Democratic convention in Denver—to support Barack Obama, but also to make sure, as I said, "that we will break the old gridlock and guarantee that every American…will have decent, quality health care as a fundamental right and not just a privilege." For four decades I have carried this cause—from the floor of the United States Senate to every part of this country. It has never been merely a question of policy; it goes to the heart of my belief in a just society. Now the issue has more meaning for me—and more urgency—than ever before. But it's always been deeply personal, because the importance of health care has been a recurrent lesson throughout most of my 77 years.

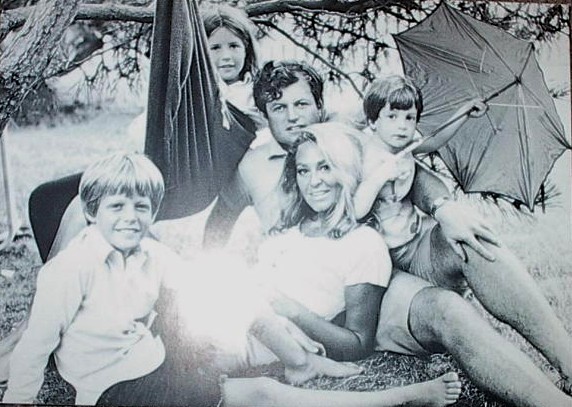

Nothing I'm enduring now can compare to hearing that my children were seriously ill. In 1973, when I was first fighting in the Senate for universal coverage, we learned that my 12-year-old son Teddy had bone cancer. He had to have his right leg amputated above the knee. Even then, the pathology report showed that some of the cancer cells were very aggressive. There were only a few long-shot options to stop it from spreading further. I decided his best chance for survival was a clinical trial involving massive doses of chemotherapy. Every three weeks, at Children's Hospital Boston, he had to lie still for six hours while the fluid dripped into his arm. I remember watching and praying for him, all the while knowing how sick he would be for days afterward.

During those many hours at the hospital, I came to know other parents whose children had been stricken with the same deadly disease. We all hoped that our child's life would be saved by this experimental treatment. Because we were part of a clinical trial, none of us paid for it. Then the trial was declared a success and terminated before some patients had completed their treatments. That meant families had to have insurance to cover the rest or pay for them out of pocket. Our family had the necessary resources as well as excellent insurance coverage. But other heartbroken parents pleaded with the doctors: What chance does my child have if I can only afford half of the prescribed treatments? Or two thirds? I've sold everything. I've mortgaged as much as possible. No parent should suffer that torment. Not in this country. Not in the richest country in the world.

That experience with Teddy made it clear to me, as never before, that health care must be affordable and available for every mother or father who hears a sick child cry in the night and worries about the deductibles and copays if they go to the doctor. But that was just one medical crisis. My family, like every other, has faced many—at every stage of life. I think of my parents and the medical care they needed after their strokes. I think of my son Patrick, who suffered serious asthma as a child and sometimes had to be rushed to the hospital for treatment. (For this reason, we had no dogs in the house when Patrick was young.) I think of my daughter, Kara, diagnosed with lung cancer in 2002. Few doctors were willing to try an operation. One did—and after that surgery and arduous rounds of chemotherapy and radiation, she's alive and healthy today. My family has had the care it needed. Other families have not, simply because they could not afford it.

I have seen letters and e-mails from many of these less fortunate Americans. In their pleas, there's always dignity, but too often desperation. "Our school is closing in June of 2010, which means that I will be losing my job and my health insurance," writes Mary Dunn, a 58-year-old schoolteacher in Eden, S.D. "I am a Type I diabetic, and I had heart bypass surgery in 2005. My husband is also a teacher [here], so we will both be losing insurance. I am exploring options and have been told that I cannot stay on our group policy or transfer to another policy after our jobs cease because of my medical condition. What am I to do after 39 years of teaching to acquire adequate health coverage?" Dunn also serves as mayor of Eden, for which she is paid $45 a month with no health benefits.

How will we, as a nation, answer her? I've heard countless such stories, including one from the family of Cassandra Wilson, a 14-year-old who once was a competitive ice skater. She's uninsured because she has petit mal seizures, often 200 times a day. Her parents have run up $30,000 on their credit cards. They've sold her skating equipment on eBay to pay for her care.

These two cases represent only those patients who lack coverage. We also need to find answers for the increasing number of Americans whose insurance costs too much, covers too little, and can be too easily revoked when they face the most serious illnesses.

Our response to these challenges will define our character as a country. But the challenges themselves—and the demands for reform—are not new. In 1912, when Theodore Roosevelt ran for a third term as president, the platform of his newly created Progressive Party called for national health insurance. Harry Truman proposed it again more than 30 years after Roosevelt was defeated. The plan was attacked, not for the last time, as "socialized medicine," and members of Truman's White House staff were branded "followers of the Moscow party line."

For the next generation, no one ventured to tread where T.R. and Truman fell short. But in the early 1960s, a new young president was determined to take a first step—to free the elderly from the threat of medical poverty. John Kennedy called Medicare "one of the most important measures I have advocated." He understood the pain of injury and illness: as a senator, he had almost died after surgery to repair a back injury sustained during World War II, an injury that would plague him all of his life. I was in college as he recuperated and learned to walk without crutches at my parents' winter home in Florida. I visited often, and we spent afternoons painting landscapes and seascapes. (It was a competition: at dinner after we finished, we would ask family members to decide whose painting was better.) I saw how the pain would periodically hit him as we were painting; he'd have to put down his brush for a while. And I saw, too, how hard he fought as president to pass Medicare. It was a battle he didn't have the opportunity to finish. But I was in the Senate to vote for the Medicare bill before Lyndon Johnson signed it into law—with Harry Truman at his side. In the Senate, I viewed Medicare as a great achievement, but only a beginning. In 1966, I visited the Columbia Point Neighborhood Health Center in Boston; it was a pilot project providing health services to low-income families in the two-floor office of an apartment building. I saw mothers in rocking chairs, tending their children in a warm and welcoming setting. They told me this was the first time they could get basic care without spending hours on public transportation and in hospital waiting rooms. I authored legislation, which passed a few months later, establishing the network of community health centers that are all around America today.

Some years later, I decided the time was right to renew the quest for universal and affordable coverage. When I first introduced the bill in 1970, I didn't expect an easy victory (although I never suspected that it would take this long). I eventually came to believe that we'd have to give up on the ideal of a government-run, single-payer system if we wanted to get universal care. Some of my allies called me a sellout because I was willing to compromise. Even so, we almost had a plan that President Richard Nixon was willing to sign in 1974—but that chance was lost as the Watergate storm swept Washington and the country, and swept Nixon out of the White House. I tried to negotiate an agreement with President Carter but became frustrated when he decided that he'd rather take a piecemeal approach. I ran against Carter, a sitting president from my own party, in large part because of this disagreement. Health reform became central to my 1980 presidential campaign: I argued then that the issue wasn't just coverage but also out-of-control costs that would ultimately break both family and federal budgets, and increasingly burden the national economy. I even predicted, optimistically, that the business community, largely opposed to reform, would come around to supporting it.

That didn't happen as soon as I thought it would. When Bill Clinton returned to the issue in the first years of his presidency, I fought the battle in Congress. We lost to a virtually united front of corporations, insurance companies, and other interest groups. The Clinton proposal never even came to a vote. But we didn't just walk away and do nothing—even though Republicans were again in control of Congress. We returned to a step-by-step approach. With Sen. Nancy Landon Kassebaum of Kansas, the daughter of the 1936 Republican presidential nominee, I crafted a law to make health insurance more portable for those who change or lose jobs. It didn't do enough to fully guarantee that, but we made progress. I worked with my friend Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah, the Republican chair of our committee, to enact CHIP, the Children's Health Insurance Program; today it covers more than 7 million children from low-income families, although too many of them could soon lose coverage as impoverished state governments cut their contributions.

Incremental measures won't suffice anymore. We need to succeed where Teddy Roosevelt and all others since have failed. The conditions now are better than ever. In Barack Obama, we have a president who's announced that he's determined to sign a bill into law this fall. And much of the business community, which has suffered the economic cost of inaction, is helping to shape change, not lobbying against it. I know this because I've spent the past year, along with my staff, negotiating with business leaders, hospital administrators, and doctors. As soon as I left the hospital last summer, I was on the phone, and I've kept at it. Since the inauguration, the administration has been deeply involved in the process. So have my Senate colleagues—in particular Max Baucus, the chair of the Finance Committee, and my friend and partner in this mission, Chris Dodd. Even those most ardently opposed to reform in the past have been willing to make constructive gestures now.

To help finance a bill, the pharmaceutical industry has agreed to lower prices for seniors, not only saving them money for prescriptions but also saving the government tens of billions in Medicare payments over the next decade. Senator Baucus has agreed with hospitals on more than $100 billion in savings. We're working with Republicans to make this a bipartisan effort. Everyone won't be satisfied—and no one will get everything they want. But we need to come together, just as we've done in other great struggles—in World War II and the Cold War, in passing the great civil-rights laws of the 1960s, and in daring to send a man to the moon. If we don't get every provision right, we can adjust and improve the program next year or in the years to come. What we can't afford is to wait another generation.

I long ago learned that you have to be a realist as you pursue your ideals. But whatever the compromises, there are several elements that are essential to any health-reform plan worthy of the name.

First, we have to cover the uninsured. When President Clinton proposed his plan, 33 million Americans had no health insurance. Today the official number has reached 47 million, but the economic crisis will certainly push the total higher. Unless we act now, within a few years, 55 million Americans could be left without coverage even as the economy recovers.

All Americans should be required to have insurance. For those who can't afford the premiums, we can provide subsidies. We'll make it illegal to deny coverage due to preexisting conditions. We'll also prohibit the practice of charging women higher premiums than men, and the elderly far higher premiums than anyone else. The bill drafted by the Senate health committee will let children be covered by their parents' policy until the age of 26, since first jobs after high school or college often don't offer health benefits.

To accomplish all of this, we have to cut the costs of health care. For families who've seen health-insurance premiums more than double—from an average of less than $6,000 a year to nearly $13,000 since 1999—one of the most controversial features of reform is one of the most vital. It's been called the "public plan." Despite what its detractors allege, it's not "socialism." It could take a number of different forms. Our bill favors a "community health-insurance option." In short, this means that the federal government would negotiate rates—in keeping with local economic conditions—for a plan that would be offered alongside private insurance options. This will foster competition in pricing and services. It will be a safety net, giving Americans a place to go when they can't find or afford private insurance, and it's critical to holding costs down for everyone.

We also need to move from a system that rewards doctors for the sheer volume of tests and treatments they prescribe to one that rewards quality and positive outcomes. For example, in Medicare today, 18 percent of patients discharged from a hospital are readmitted within 30 days—at a cost of more than $15 billion in 2005. Most of these readmissions are unnecessary, but we don't reward hospitals and doctors for preventing them. By changing that, we'll save billions of dollars while improving the quality of care for patients.

Social justice is often the best economics. We can help disabled Americans who want to live in their homes instead of a nursing home. Simple things can make all the difference, like having the money to install handrails or have someone stop by and help every day. It's more humane and less costly—for the government and for families—than paying for institutionalized care. That's why we should give all Americans a tax deduction to set aside a small portion of their earnings each month to provide for long-term care.

Another cardinal principle of reform: we have to make certain that people can keep the coverage they already have. Millions of employers already provide health insurance for their employees. We shouldn't do anything to disturb this. On the contrary, we need to mandate employer responsibility: except for small businesses with fewer than 25 employees, every company should have to cover its workers or pay into a system that will.

We need to prevent disease and not just cure it. (Today 80 percent of health spending pays for care for the 20 percent of Americans with chronic illnesses like diabetes, cancer, or heart disease.) Too many people get to the doctor too seldom or too late—or know too little about how to stay healthy. No one knows better than I do that when it comes to advanced, highly specialized treatments, America can boast the best health care in the world—at least for those who can afford it. But we still have to modernize a system that doesn't always provide the basics.

I've heard the critics complain about the costs of change. I'm confident that at the end of the process, the change will be paid for—fairly, responsibly, and without adding to the federal deficit. It doesn't make sense to negotiate in the pages of NEWSWEEK, but I will say that I'm open to many options, including a surtax on the wealthy, as long as it meets the principle laid down by President Obama: that there will be no tax increases on anyone making less than $250,000 a year. What I haven't heard the critics discuss is the cost of inaction. If we don't reform the system, if we leave things as they are, health-care inflation will cost far more over the next decade than health-care reform. We will pay far more for far less—with millions more Americans uninsured or underinsured.

This would threaten not just the health of Americans but also the strength of the American economy. Health-care spending already accounts for 17 percent of our entire domestic product. In other advanced nations, where the figure is around 10 percent, everyone has insurance and health outcomes that are equal or better than ours. This disparity undermines our ability to compete and succeed in the global economy. General Motors spends more per vehicle on health care than on steel.

We will bring health-care reform to the Senate and House floors soon, and there will be a vote. A century-long struggle will reach its climax. We're almost there. In the meantime, I will continue what I've been doing—making calls, urging progress. I've had dinner twice recently at my home in Hyannis Port with Senator Dodd, and when President Obama called me during his Rome trip after meeting with the Pope, much of our discussion was about health care. I believe the bill will pass, and we will end the disgrace of America as the only major industrialized nation in the world that doesn't guarantee health care for all of its people.

At another Democratic convention, in arguing for this cause, I spoke of the insurance coverage senators and members of Congress provide for themselves. That was 1980. In the last year, I've often relied on that Congressional insurance. My wife, Vicki, and I have worried about many things, but not whether we could afford my care and treatment. Each time I've made a phone call or held a meeting about the health bill—or even when I've had the opportunity to get out for a sail along the Massachusetts coast—I've thought in an even more powerful way than before about what this will mean to others. And I am resolved to see to it this year that we create a system to ensure that someday, when there is a cure for the disease I now have, no American who needs it will be denied it.

Go to:

http://www.newsweek.com/id/207406/page/1