Senator Edward M. Kennedy, who carried aloft the torch of a Massachusetts dynasty and a liberal ideology to the citadel of Senate power, but whose personal and political failings may have prevented him from realizing the ultimate prize of the presidency, died late Tuesday night. The senator was 77.

Overcoming a history of family tragedy, including the assassinations of a brother who was president and another who sought the presidency, Senator Kennedy seized the role of being a “Senate man.’’ He became a Democratic titan of Washington who fought for the less fortunate, who crafted unlikely deals with conservative Republicans, and who ceaselessly sought support for universal health coverage.

“Teddy,’’ as he was known to intimates, constituents, and even his fiercest enemies, was an unwavering symbol to the left and the right - the former for his unapologetic embrace of liberalism, and latter for his value as a political target. But with his fiery rhetoric, his distinctive Massachusetts accent, and his role as representative of one of the nation’s best-known political families, he was widely recognized as an American original. In the end, some of those who might have been his harshest political enemies, including former President George W. Bush, found ways to collaborate with the man who was called the “last lion’’ of the Senate.

Senator Kennedy’s White House aspirations may have been undercut by his actions on the night he drove off a bridge at Chappaquiddick Island and failed to promptly report the accident in which Mary Jo Kopechne, who had worked for his brother Robert, died. When Kennedy nonetheless later sought to wrest the presidential nomination from an incumbent Democrat, Jimmy Carter, he failed. But that failure prompted him to reevaluate his place in history, and he dedicated himself to fulfilling his political agenda by other means, famously saying, “the dream shall never die.’’

Those causes endure today and remain at the forefront of the American political stage, evidenced most recently by the fight for universal health care.

He was the youngest child of a famous family, but his legacy derived from quiet subcommittee meetings, conference reports, and markup sessions. The result of his efforts meant hospital care for a grandmother, a federal loan for a working college student, or a better wage for a dishwasher.

With a family saga that blended Greek tragedy and soap opera, the Kennedys fascinated America and the world for half a century. “I have every expectation of living a long and worthwhile life,’’ Senator Kennedy said in 1994. Such an expectation contrasted with the fate of his brothers.

Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. was killed in 1944 on a World War II bombing mission. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. Senator Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated while campaigning for president in Los Angeles in 1968.

Ted Kennedy’s congressional career was remarkable not only for its accomplishments, but for its length of 47 years. Massachusetts voters installed him in the Senate nine times - starting with a special election in 1962.

Since the doors of the Senate first opened in 1789, only Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia and the late Strom Thurmond of South Carolina served longer.

Senator Kennedy brought to the Senate a trait his brothers lacked - patience - and what his mother called a “ninth-child talent,’’ a blend of toughness and tact.

Birth of a political legend The ninth child of Joseph P. and Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy was born on the 200th anniversary of George Washington’s birth, Feb. 22, 1932. His brother Jack, then at the Choate School in Connecticut, wrote to his parents, asking to be godfather and urging the new arrival to be baptized George Washington Kennedy.

The parents agreed to the first request but named the child Edward Moore Kennedy, after one of his father’s assistants. Part of his boyhood was spent in London, where his father was US ambassador to Great Britain.

After nine schools on two continents, he entered Milton Academy in 1946, joined the drama club and the debating society, played tennis and football, and maintained mostly midlevel grades, including in Spanish, a subject that would trouble him at Harvard College, where, in 1951, he asked a friend to take a Spanish exam for him.

A proctor recognized the substitute, and both students were expelled but were told they could return to Harvard if they showed evidence of “constructive and responsible citizenship.’’

The incident would become the first of several episodes creating public doubts about his character. The Spanish exam resurfaced in 1962, when some Harvard professors opposed his nomination for the US Senate. President Kennedy negotiated the release of expulsion details to the Globe, and Ted Kennedy’s confession diminished its political impact.

After the Harvard expulsion, he volunteered for the military, and Private Kennedy met a more diverse group of people at Fort Dix, N.J., than he would have in Cambridge. His father helped arrange an assignment, during fighting in Korea, to NATO headquarters in Paris.

In 1954, after two years in the Army, Ted Kennedy returned to Harvard, became a resident of Winthrop House, as were his brothers, and an end on the football team, for which he scored a touchdown in a losing effort against Yale.

He graduated from Harvard in 1956 and the University of Virginia Law School three years later.

At a Kennedy family event at Manhattanville College, the alma mater of his sisters, he met Joan Bennett, the daughter of a New York advertising executive. They married in 1958, the same year he managed the Senate reelection campaign of his brother John against Vincent J. Celeste of East Boston. The outcome was not in doubt; Ted’s assignment was to steer the incumbent to a victory big enough to impress national Democratic Party bosses. The victory margin was 857,000, the highest in the Commonwealth’s history.

In 1959, Ted Kennedy headed west to help his brother’s presidential campaign. At the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles in 1960, when Wyoming cinched JFK’s nomination, Ted Kennedy stood among the state’s delegates, cheering them. During the 1960 election against Republican Richard Nixon, Ted Kennedy considered moving from Massachusetts if JFK lost the White House. Instead, his brother’s win intertwined the destinies of Edward Moore Kennedy and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

On to the Senate John F. Kennedy declared in his inaugural address that “the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans.’’ This iconography would play out over generations of Kennedys.

Upon winning the presidency, John Kennedy persuaded Governor Foster Furcolo to fill his vacant Senate seat by appointing Benjamin A. Smith II, the mayor of Gloucester who was a friend of the president at Harvard.

On March 14, 1962, after he attained the constitutional age of 30 to be eligible for election to the Senate, Edward Kennedy announced his candidacy for the unexpired term of his brother. His only public experience was a year as assistant district attorney of Suffolk County, and he had to take on two Massachusetts dynasties.

In the special election, he first faced state Attorney General Edward J. McCormack Jr., the nephew of US House Speaker John W. McCormack.

On several issues, including nuclear weapons and civil liberties, McCormack was more liberal than his opponent, but the campaign was not ideological.

At a debate in South Boston, McCormack ridiculed the young Ted, saying the senatorial job “should be merited, not inherited.’’ Pointing his finger at his opponent, he said: “If his name were Edward Moore, with his qualifications - with your qualifications, Teddy - if it was Edward Moore, your candidacy would be a joke.’’

Ted Kennedy looked pained and shocked. His silence created a wave of sympathy.

“Some say Eddie came on too strong, others still say he was right on the mark; I agree with both of them,’’ Senator Kennedy said at McCormack’s funeral 35 years later.

Ted Kennedy went on to win 69 percent of the primary vote and then to defeat George C. Lodge, the son of the former Republican senator, in the general election. After his November victory, he was sworn in swiftly, to gain more senatorial seniority. He took the oath from Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson on Nov. 7, 1962.

Even with a brother in the White House and another as attorney general, a freshman senator was supposed to work diligently for local concerns and to perform committee work in patient obscurity. Senator Kennedy did so, taking on his brother’s legislative concerns on refugees and immigrants. He sought “more for Massachusetts’’ by pursuing fishery development and a Cambridge electronics research center for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Disasters strike On Nov. 22, 1963, Senator Kennedy was presiding over the chamber, a chore assigned to freshman members, when a messenger arrived at the rostrum with the news from Dallas. After confirming with the White House the president’s assassination, Senator Kennedy and his sister, Eunice, flew to Hyannis Port to deliver the news to their father. Joseph P. Kennedy had suffered a stroke in 1961 and could not speak or walk.

The senator called the new president that night. “I want you to know how much I appreciate your thoughts for my mother and family,’’ he said. Johnson maintained more cordial relations with the youngest Kennedy than with his siblings, Robert in particular.

In Congress, Senator Kennedy did not deliver his first major address from the floor until April 1964. The subject was civil rights, the unfinished business of his slain brother.

Eager to win a full six-year term later that year, Senator Kennedy planned to visit Springfield to accept the endorsement of the Democratic state convention. On the night of June 19, after casting votes on final passage of a civil rights bill, Senator Kennedy and the convention’s keynote speaker, Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana, boarded a twin-engine private plane en route to Barnes Municipal Airport in Westfield.

In heavy fog, the aircraft crashed in an apple orchard, killing the pilot and a Kennedy aide. Senator Kennedy sustained three broken vertebrae, fractured ribs, a punctured lung, a bruised kidney, and internal hemorrhaging.

During a visit to the hospital, Robert Kennedy muttered mordantly, “I guess the reason my mother and father had so many children is so that some would survive.’’

Political chores were left to Joan, who shuttled between campaign events and hospital visits. After a six-month recuperation, Senator Kennedy was released, but back injuries would cause him pain for the rest of his life. The Republican opponent was Howard Whitmore, the former mayor of Newton, who said, “My opponent is flat on his back, and, from a gentleman’s standpoint, I can’t campaign against that.’’ Senator Kennedy was reelected with 74.3 percent of the vote.

In that same election, voters of New York elected Robert F. Kennedy as their senator. In 1965, on the first day of the 89th Congress, the Kennedy brothers were sworn in together.

The siblings teased each other frequently but seldom diverged in their liberal voting patterns. Robert had seniority in the family and was a former US attorney general, but Edward took the lead on legal issues such as repealing the poll tax.

Oceanography, historic preservation, immigration, voting rights - these issues also occupied the junior senator from Massachusetts in 1965. But he made more news by sponsoring the nomination of Boston Municipal Court Judge Francis X. Morrissey, a friend of the family, for a seat on the federal district court.

Undaunted by the opposition of the American Bar Association, Senator Kennedy sent Morrissey’s name to the White House, and President Johnson nominated him. The hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee were stormy, with the Senate minority leader, Everett M. Dirksen of Illinois, mocking Morrissey’s credentials and with ABA officials calling him unqualified.

Republicans found ammunition in stories in the Globe disputing Morrissey’s assertions that he attended law school at Boston College and Southern Law School in Athens, Ga. Senator Kennedy’s vote-counting abilities led him to withdraw his friend’s name.

In October 1965, the senator made his first visit to South Vietnam, a nation that would profoundly affect the United States, President Johnson, and the Kennedys.

The longest war in American history fulfilled a promise inherent in JFK’s inaugural speech in 1961 that “we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and success of liberty.’’

By 1967, antiwar marches and rallies were proliferating and on Nov. 30 Senator Eugene J. McCarthy of Minnesota agreed, after Robert Kennedy declined, to challenge Johnson in the 1968 Democratic primaries. After McCarthy won 42 percent of the New Hampshire vote and before Johnson would bow out, Robert Kennedy reconsidered and entered the contest.

In June, after winning the California primary, Robert Kennedy was assassinated. At St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, the voice of the surviving Kennedy brother cracked as he eulogized Robert as “a good and decent man, who . . . saw war and tried to stop it.’’ Senator Kennedy became the surrogate father of his brothers’ children and a patriarch of the growing clan.

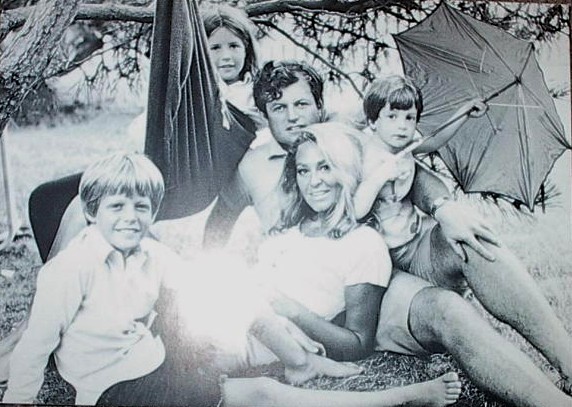

His own family had grown with the birth of Patrick Joseph Kennedy a year before. Kara Anne had been born in 1960 and Edward Jr. in 1961. In addition to his children and his wife, Vicki, Senator Kennedy leaves two stepchildren, Caroline and Curran Raclin, his sister, Jean Kennedy Smith, and four grandchildren.

Vietnam dominated the 1968 Democratic National Convention, as did speculation about Senator Kennedy’s intentions. “Like my brothers before me, I pick up a fallen standard,’’ he said at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester a few weeks before the convention. “Sustained by the memory of our priceless years together, I shall try to carry forward that special commitment to jus tice, to excellence, and to the courage that distinguished their lives.’’

But the Capitol, not the White House, seemed the focus of his intentions. The senator said he would not run for president or vice president. After Richard Nixon defeated Hubert H. Humphrey in a close contest, Senator Kennedy surprised many in Washington by running for majority whip. By a 31-26 vote, he defeated the incumbent, another son of a famous political dynasty, Senator Russell B. Long of Louisiana.

On a cold January night, before celebrating at his home in McLean, Va., the 36-year-old senator drove to Arlington National Cemetery, where the gravesite of Robert was under construction, next to John’s.

Tragedy and turmoil Majority leader Mike Mansfield of Montana welcomed his new assistant, saying, “Of all the Kennedys, the senator is the only one who was and is a real Senate man.’’ Senator Kennedy mobilized Democrats against what he called the “folly’’ of an antiballistic missile system proposed by President Nixon and continued to oppose the war in Vietnam. On July 18, 1969, Mansfield predicted that his colleague would not run for president in 1972, saying “He’s in no hurry. He’s young. He likes the Senate.’’

On that same day, Senator Kennedy arrived on an island that his actions would make notorious. On Chappaquiddick, across a narrow inlet from Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard, six young women who had worked on Robert Kennedy’s campaign gathered for a reunion at a rented cottage. Senator Kennedy’s marriage was already troubled, and he had been seen in the company of other glamorous women. But the women at Chappaquiddick were all serious, professional political operatives.

Mary Jo Kopechne, 28, had worked for RFK’s Senate office. A passenger in a car driven by Ted Kennedy, she drowned after the car skidded off a bridge. Senator Kennedy failed to report the accident for 10 hours. The crash gave him a minor concussion and a major personal and political crisis.

As American astronauts walked on the moon, fulfilling a JFK pledge, Chappaquiddick was front-page news across the globe. The senator was unable to explain the accident for days. After consulting in Hyannis Port with his brothers’ advisers and speechwriters, he gave a televised speech a week later. He praised Kopechne and attacked “ugly speculation about her character,’’ wondered aloud “whether some awful curse did actually hang over the Kennedys,’’ then asked Massachusetts voters whether he should resign. They replied overwhelmingly: No.

His critics snarled that Senator Kennedy “got away with it’’ at Chappaquiddick, but the price he paid in personal grief was as high as the cost in presidential politics. During the Cold War, voters expected quick and cool judgment from presidents. Senator Kennedy, in effect, disqualified himself when he confessed on television that he should have alerted police immediately: “I was overcome, I’m frank to say, by a jumble of emotions: grief, fear, doubt, exhaustion, panic, confusion, and shock.’’

He returned to his work in the Senate and in December 1969 began a long campaign “to move now to establish a comprehensive national health care insurance program.’’ He also led the effort to give 18-year-olds the right to vote.

After winning reelection in 1970 with 62 percent of the vote, he found how Chappaquiddick reverberated in the Senate chamber. In January 1971, Senator Byrd unseated Senator Kennedy as majority whip by a 31-24 vote of the Democratic caucus.

Senator Kennedy privately thanked Byrd years later because the loss made him concentrate on committee work in health care, refugees, civil rights, the judiciary, and foreign policy, areas in which he would leave a lasting imprint.

Also in 1971, he made one of his strongest statements on Northern Ireland amid an explosion of political violence, saying “Ulster is becoming Britain’s Vietnam,’’ which the British prime minister called an “ignorant outburst.’’ Years later, on St. Patrick’s Day in 1977, Senator Kennedy and other leaders would ask Irish-Americans to shun the violence of the Irish Republican Army. It was called “the big four’’ statement, after Senator Kennedy and Speaker Thomas P. O’Neill Jr. of Massachusetts, and Governor Hugh L. Carey and Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York.

As he was rebuilding his stature in the chamber in the fall of 1973, Senator Kennedy and his wife, Joan, received devastating news. Their 12-year-old son, Edward Jr., had cancer and his leg had to be amputated. Although Ted Jr. overcame the cancer, the crisis cooled the senator’s ambitions about running for president in 1976.

Hometown political issues also took a toll. In Boston, crowds vehemently protested a school desegregation busing order by a family friend, federal Judge W. Arthur Garrity. The issue dogged Senator Kennedy throughout 1974 and 1975. In 1976, although challenged in the Democratic primary by two antibusing candidates, he won with 74 percent and in November chalked up a reelection victory tally of 69 percent.

The run for the White House The election of 1976 would bring a Democrat back into the White House. Jimmy Carter of Georgia, however, was not a Kennedy Democrat. The ideological divide between the two was profound. Even though the Massachusetts senator had pursued some pro-business policies such as deregulating airlines, he believed in an active government that some would call intrusive; Carter tended to be more conservative. Senator Kennedy thought Carter’s health care programs were timid. The president sometimes resented Senator Kennedy’s celebrity status, especially when foreign leaders consulted with the senator.

The divisions only widened over Carter’s first term. When the Democrats held a mid-term conference in Memphis in December 1978, it was dominated by the senator’s nautical metaphor. “Sometimes a party must sail against the wind,’’ he said. “We cannot afford to drift or lie at anchor. We cannot heed the call of those who say it is time to furl the sail.’’ Carter’s response to a group of Democratic congressmen: If Senator Kennedy did challenge him in the next election, “I’ll whip his ass.’’

Shortly before he announced that challenge, however, Senator Kennedy stumbled in an interview with CBS’s Roger Mudd. The commentator’s question seemed simple: Why was he running for president.

“Well, I’m - were I to make the announcement and to run,’’ Senator Kennedy said, “the reasons that I would run is because I have a great belief in this country. That it is - there’s more natural resources than any nation in the world; the greatest education population in the world; the greatest technology of any country in the world; the greatest capacity for innovation in the world; and the greatest political system in the world.’’

His responses to questions about Chappaquiddick sounded rehearsed, and the interview was widely considered a disaster. He would not recover.

On Nov. 7, 1979, three days after the interview was broadcast, the 47-year-old senator formally declared his candidacy for the 1980 Democratic presidential nomination, saying he was “compelled by events and by my commitment to public life.’’

“For many months, we have been sinking into crisis. Yet we hear no clear summons from the center of power,’’ he said, standing on the stage of Faneuil Hall before a giant painting of Daniel Webster, a longtime US senator from Massachusetts who never became president.

Unable to persuade Democrats to abandon a Democratic president, Senator Kennedy won only 10 of the 35 presidential primaries. In August, he reluctantly endorsed Carter at the Democratic National Convention in New York and offered his own anthem to the Democratic Party. He cited Jefferson, Jackson, Franklin Roosevelt, and those he had met at “the closed factories and the stalled assembly lines.’’ After congratulating Carter, he said, “For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die.’’

The lion of the Senate In 1981, because of Ronald Reagan’s coattails, Senator Kennedy was in the Senate minority for the first time. But he was accustomed to reaching across the aisle for support. Throughout his career, Senator Kennedy’s name animated Republican fund-raising efforts. In reality, the GOP’s bete noire cooperated with party leaders from Barry Goldwater to John McCain, a list that included conservative stalwarts Robert Dole, Orrin Hatch, and Alan Simpson.

Senator Kennedy’s success owed more to craftsmanship than charm, more to diligence than blarney. In 1985, outside the hearing room of the Armed Service Committee, a reporter encountered Senator John Warner, a Republican of Virginia, who spontaneously volunteered praise of his liberal colleague from Massachusetts: “This man works as hard as anyone. When he knows his subject, he really knows it. He listens, he learns, and he’s an asset to this committee.’’

In the 1960s, the young senator had learned a lesson from Senator Philip Hart of Michigan, who said of the Senate, “you measure accomplishments not by climbing mountains, but by climbing molehills.’’

In the 1980s, those molehills amounted to the renewal of the Voting Rights Act; an overhaul of federal job training (co-sponsored by a freshman senator from Indiana, Dan Quayle); and, with his Massachusetts colleagues from the House, Speaker O’Neill and Representative Edward P. Boland, a steady assault on Reagan administration policies in Central America.

In 1985, Senator Kennedy renounced presidential ambitions, saying to Bay State voters, “I will run for reelection to the Senate. I know that this decision means that I may never be president. But the pursuit of the presidency is not my life. Public service is.’’

“When he finally lifted the curse from himself that Kennedys had to be president, he truly became a legislator,’’ said Simpson, a Wyoming Republican who served 18 years in the Senate with Kennedy. “In fact, he immersed himself in legislation.’’

Others in the Kennedy clan would join him in such efforts.

In 1986, he watched with pride as his nephew Joseph won the seat vacated by O’Neill and in 1994 as his son, Patrick, won a congressional seat from Rhode Island.

Not all family matters, however, were a source of pride. In 1991, the senator had to testify in Palm Beach about rape charges brought against his nephew William Kennedy Smith in the aftermath of a drinking party organized by Senator Kennedy. The incident embarrassed the senator into silence during judiciary committee hearings into allegations of sexist conduct against Clarence Thomas, later confirmed as a Supreme Court justice.

Senator Kennedy’s behavior continued to provide fodder to gossip sheets. His reputation as a roustabout lingered until, years after he and Joan divorced in 1982, Senator Kennedy met Victoria Reggie, a Washington lawyer and divorced mother of two who was 22 years younger than the senator. They wed in 1992 and began a partnership that brought equilibrium and focus to his life.

In 1994, when Republicans recaptured the House for the first time in 40 years, no Democrat was safe, even the leading lion of liberalism in Massachusetts. A Republican businessman, Mitt Romney, captured the attention of some Bay Staters until, in a Faneuil Hall debate, Senator Kennedy proved his mastery of the issues.

For the senator, it was a relatively close call. He won with 58 percent of the vote, his smallest margin since his first election in 1962.

Senator Kennedy returned to form in subsequent reelections, winning by lopsided margins in 2000 and 2006 over lesser Republican competitors.

In Washington, he continued to work on issues subtle and unsubtle. In the latter category was one of his favorites, raising the minimum wage, a perennial struggle because its recipients lacked the Washington lobbies that support business interests.

As he had done for more than half his time in Washington, Senator Kennedy launched his crusade on behalf of those who daily do the menial work that make everyone else’s day cleaner, brighter, and safer. “The minimum wage,’’ he often said, “was one of the first and is still one of the best antipoverty programs we have.’’

During the administration of Republican George W. Bush, Senator Kennedy led the Senate’s antiwar faction as the president pressed Congress for the authorization to use military force against Iraq.

In a speech at Johns Hopkins University about a year after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Senator Kennedy said the administration had failed to make the case for a preemptive attack.

“I do not accept the idea that trying other alternatives is either futile or perilous, that the risks of waiting are greater than the risk of war,’’ Senator Kennedy said, recalling his brother’s restraint in dealing with the Soviet Union during the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962.

Two weeks later, the House and Senate passed the Iraq war resolution by wide margins. Senator Kennedy was among 21 Democrats who voted in opposition.

But Senator Kennedy displayed a willingness to be helpful when he thought Bush was right. He was a force behind the Bush administration’s chief domestic policy achievement in its first term, No Child Left Behind, the sweeping education bill that mandated testing to measure student progress. Senator Kennedy was a lead author and attended the signing ceremony in February 2002.

When Bush introduced him, the president said: “He is a fabulous United States senator. When he’s against you, it’s tough. When he’s with you, it is a great experience.’’

In early 2008, shortly before his cancer diagnosis, Senator Kennedy surprised much of the political world by endorsing Senator Barack Obama for president over Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton. The endorsement was seen as a passing of the Kennedy torch to the man aspiring to be the nation’s first black president.

With less than two weeks before Obama would face the far better-known Clinton in ’’Super Tuesday’’ contests in about half the states of the country, Senator Kennedy’s endorsement came at an optimal moment. Obama held Clinton to a draw in those contests, setting him up for his nomination and election as president.

Though Obama lost the Massachusetts primary to Clinton in what some saw as a sign of Senator Kennedy’s declining influence many analysts believed that Senator Kennedy’s support helped spur Obama to major victories in states where delegates were chosen in caucuses of party activists, many of whom had decades of allegiance to the longtime senator.

Despite his illness, Senator Kennedy made a forceful appearance at the Democratic convention in Denver, exhorting his party to victory and declaring that the fight for universal health insurance had been “the cause of my life.’’

He pursued that cause vigorously, and even as his health declined, he spent days reaching out to colleagues to win support for a sweeping overhaul; when members of Obama’s administration questioned the president’s decision to spend so much political capital on the seemingly intractable health care issue, Obama reportedly replied, “I promised Teddy.’’

Go to:

http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2009/08/26/kennedy_dead_at_77/

FEEL FREE TO LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS AFTER READING THE MOST RECENT KENNEDY NEWS!!!

Monday, August 31, 2009

Friday, July 31, 2009

Spokesman: Kennedy talking health care with Obama

Ailing Senator Ted Kennedy, trying to help push health care reform as he recovers at his Massachusetts home from brain cancer, is talking to President Obama about the legislation.

Kennedy spokesman Anthony Coley confirmed to CNN that the President and Kennedy (D-Massachusetts) have spoken twice in the last two weeks.

Coley said Kennedy is closely watching developments on Capitol Hill from his home on Cape Cod. He monitors health care reform congressional hearings on television and reads daily news clips on the issue sent to him by his office staff, Coley said.

Meanwhile, the 77-year-old senator was spotted sailing this weekend in the waters near the Kennedy family compound in Hyannis Port.

Kennedy boarded his sailboat the "Mya" late Sunday afternoon, wearing an orange jacket, blue jeans, tennis shoes, sunglasses, and a white cap to protect his head and neck. He was surrounded by family members, including sons Ted Kennedy Jr. and Rep. Patrick Kennedy.

Photographer David G. Curren said Kennedy appeared stronger than a week earlier. Kennedy rode a golf cart to get to the boat at the Hyannis Port Yacht Club. But he was able to stand up and get onto the boat with someone holding on to him.

Curren said Kennedy was in good spirits, and the photographerer said he was struck by Kennedy's wide smile. He said Kennedy goes on the water whenever he can, "and you can tell it's what he loves to do. He's generally smiling" when he sails.

The senator and his family were on Nantucket Sound for a few hours Sunday aboard his 50-foot boat.

Go to:

http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2009/07/27/spokesman-kennedy-talking-health-care-with-obama/

Presidential Medal of Freedom for Kennedy

Senator Edward M. Kennedy received another high honor yesterday, courtesy of President Obama.

The longtime Massachusetts senator was named one of 16 recipients of this year’s Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. It is awarded to individuals who “make an especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, cultural, or other significant public or private endeavors,’’ the White House said, and “this year’s awardees were chosen for their work as agents of change.’’

Kennedy - who is battling brain cancer as Obama and Democrats in Congress try to push through the capstone of his 46-year Senate career, a healthcare overhaul - said he was “profoundly grateful’’ to Obama.

“My life has been committed to the ideal of public service, which President Kennedy wanted the Medal of Freedom to represent,’’ the senator said in a statement. “To receive it from another president who prizes that same ideal of service and inspires so many to serve is a great privilege that moves me deeply.’’

Kennedy’s award citation calls him “one of the greatest lawmakers - and leaders - of our time,’’ lauding his work on improving public schools, strengthening civil rights laws, and dedicating his career to “fighting for equal opportunity, fairness, and justice for all Americans.’’

“He has worked tirelessly to ensure that every American has access to quality and affordable healthcare, and has succeeded in doing so for countless children, seniors, and Americans with disabilities,’’ the citation says.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi congratulated Kennedy on behalf of Congress. “Few have accomplished more in a lifetime than Senator Kennedy has,’’ she said in a statement. “This award - the highest a civilian can receive - honors his steadfast commitment to the American ideal of justice.’’

Obama will present the medals, the first of his presidency, at a White House ceremony Aug. 12.

(...)

Go to:

http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2009/07/31/presidential_medal_of_freedom_for_kennedy/

The longtime Massachusetts senator was named one of 16 recipients of this year’s Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. It is awarded to individuals who “make an especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, cultural, or other significant public or private endeavors,’’ the White House said, and “this year’s awardees were chosen for their work as agents of change.’’

Kennedy - who is battling brain cancer as Obama and Democrats in Congress try to push through the capstone of his 46-year Senate career, a healthcare overhaul - said he was “profoundly grateful’’ to Obama.

“My life has been committed to the ideal of public service, which President Kennedy wanted the Medal of Freedom to represent,’’ the senator said in a statement. “To receive it from another president who prizes that same ideal of service and inspires so many to serve is a great privilege that moves me deeply.’’

Kennedy’s award citation calls him “one of the greatest lawmakers - and leaders - of our time,’’ lauding his work on improving public schools, strengthening civil rights laws, and dedicating his career to “fighting for equal opportunity, fairness, and justice for all Americans.’’

“He has worked tirelessly to ensure that every American has access to quality and affordable healthcare, and has succeeded in doing so for countless children, seniors, and Americans with disabilities,’’ the citation says.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi congratulated Kennedy on behalf of Congress. “Few have accomplished more in a lifetime than Senator Kennedy has,’’ she said in a statement. “This award - the highest a civilian can receive - honors his steadfast commitment to the American ideal of justice.’’

Obama will present the medals, the first of his presidency, at a White House ceremony Aug. 12.

(...)

Go to:

http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2009/07/31/presidential_medal_of_freedom_for_kennedy/

Wednesday, July 22, 2009

Chris Kennedy: Switching Consideration from Senate to Gov???

Christopher Kennedy is now debating whether to jump into the 2010 Democratic primary for Illinois governor, the Chicago Sun-Times has learned.

Asked to confirm that Tuesday, Kennedy's spokeswoman, Casey Madden, would only say, "Chris is keeping all his options open."

Kennedy, son of the late Sen. Robert Kennedy, currently is the CEO of the Chicago Merchandise Mart. For months, the speculation has been that he would run for U.S. Senate.

First, however, he was said to be waiting to see if Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan was in the hunt for the job. Madigan's name recognition and popularity would have been an obstacle -- not to mention the fact that the Obama White House was trying its darndest to persuade her to opt for the Senate run rather than the governor's race.

But Madigan this month stunned just about everyone by declaring she was staying put, running for election to a third term as attorney general.

And now, Kennedy is reconsidering, according to several informed sources.

But the clock is ticking.

Petitions for next February's primary begin to circulate Aug. 4.

For Kennedy, money is no object.

But despite the fact that he comes from a legendary political clan that produced a president of the United States and two U.S. Senators revered by Democratic party faithful, voters do not know this 46-year-old Kenilworth husband and father of four.

Meanwhile, Chris Kennedy risks becoming the Hamlet of Illinois politics.

"To be or not to be?" has been his persistent question.

In 2000 he seriously considered going after John Porter's former seat in the 10th Congressional District, the one currently occupied by Republican Mark Kirk, who just Monday announced a bid for U.S. Senate in 2010.

In 2002, after debating more than a year about running for governor, Kennedy didn't. Rod Blagojevich was elected.

In 2004, he considered, then rejected, a race for United States Senate. That's the seat that Barack Obama ultimately won.

And so it goes.

Kennedy, who has established himself as a solid businessman and innovative civic leader, has been a frustration to friends and politicos alike who have encouraged his ambition only to be left at the altar when he decided the time wasn't right.

Then again, Chris Kennedy has no need to please anyone but himself.

He's worth a fortune and has no need to indulge fund-raisers' yearnings to invest in a winner. He has access to a national political network of powerful people. And he has many years ahead of him to run after his kids are out of the house and on their own.

Still, as Harold Washington loved to remind, "Politics ain't beanbag."

And Chris Kennedy has neither filed for office in the past nor even held a news conference.

It takes practice and talent and no small amount of luck to pull off any race, or for that matter, to even to get appointed to something.

Caroline Kennedy proved that was true this year in New York when she appeared to be a shoo-in for Hillary Clinton's empty Senate seat. Awkward and surprisingly unprepared, she saw the Kennedy magic evaporate, and she had little choice but to withdraw.

Then again, argues one unnamed Kennedy booster, "Chris may have more time to decide than most. ... The problem for the Democratic party is races are all about the incumbent. If you've been in Springfield for the past eight [or more] years, you will get hit with millions of dollars in negative TV ads."

And so Gov. Quinn, who's been around a long time, and Comptroller Dan Hynes who's got a lengthy political resume, each have a record on which to be attacked should they, as expected, run in 2010.

Chris Kennedy, who's never run for anything, doesn't.

And won't.

Unless he finally decides to stop talking about it.

And actually run.

Asked to confirm that Tuesday, Kennedy's spokeswoman, Casey Madden, would only say, "Chris is keeping all his options open."

Kennedy, son of the late Sen. Robert Kennedy, currently is the CEO of the Chicago Merchandise Mart. For months, the speculation has been that he would run for U.S. Senate.

First, however, he was said to be waiting to see if Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan was in the hunt for the job. Madigan's name recognition and popularity would have been an obstacle -- not to mention the fact that the Obama White House was trying its darndest to persuade her to opt for the Senate run rather than the governor's race.

But Madigan this month stunned just about everyone by declaring she was staying put, running for election to a third term as attorney general.

And now, Kennedy is reconsidering, according to several informed sources.

But the clock is ticking.

Petitions for next February's primary begin to circulate Aug. 4.

For Kennedy, money is no object.

But despite the fact that he comes from a legendary political clan that produced a president of the United States and two U.S. Senators revered by Democratic party faithful, voters do not know this 46-year-old Kenilworth husband and father of four.

Meanwhile, Chris Kennedy risks becoming the Hamlet of Illinois politics.

"To be or not to be?" has been his persistent question.

In 2000 he seriously considered going after John Porter's former seat in the 10th Congressional District, the one currently occupied by Republican Mark Kirk, who just Monday announced a bid for U.S. Senate in 2010.

In 2002, after debating more than a year about running for governor, Kennedy didn't. Rod Blagojevich was elected.

In 2004, he considered, then rejected, a race for United States Senate. That's the seat that Barack Obama ultimately won.

And so it goes.

Kennedy, who has established himself as a solid businessman and innovative civic leader, has been a frustration to friends and politicos alike who have encouraged his ambition only to be left at the altar when he decided the time wasn't right.

Then again, Chris Kennedy has no need to please anyone but himself.

He's worth a fortune and has no need to indulge fund-raisers' yearnings to invest in a winner. He has access to a national political network of powerful people. And he has many years ahead of him to run after his kids are out of the house and on their own.

Still, as Harold Washington loved to remind, "Politics ain't beanbag."

And Chris Kennedy has neither filed for office in the past nor even held a news conference.

It takes practice and talent and no small amount of luck to pull off any race, or for that matter, to even to get appointed to something.

Caroline Kennedy proved that was true this year in New York when she appeared to be a shoo-in for Hillary Clinton's empty Senate seat. Awkward and surprisingly unprepared, she saw the Kennedy magic evaporate, and she had little choice but to withdraw.

Then again, argues one unnamed Kennedy booster, "Chris may have more time to decide than most. ... The problem for the Democratic party is races are all about the incumbent. If you've been in Springfield for the past eight [or more] years, you will get hit with millions of dollars in negative TV ads."

And so Gov. Quinn, who's been around a long time, and Comptroller Dan Hynes who's got a lengthy political resume, each have a record on which to be attacked should they, as expected, run in 2010.

Chris Kennedy, who's never run for anything, doesn't.

And won't.

Unless he finally decides to stop talking about it.

And actually run.

Go to:

http://blogs.suntimes.com/marin/2009/07/chris_kennedy_switching_consid.html

Monday, July 20, 2009

‘The Cause of My Life’ by Ted Kennedy

July 18, 2009

Now I face another medical challenge. Last year, I was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. Surgeons at Duke University Medical Center removed part of the tumor, and I had proton-beam radiation at Massachusetts General Hospital. I've undergone many rounds of chemotherapy and continue to receive treatment. Again, I have enjoyed the best medical care money (and a good insurance policy) can buy.

I have seen letters and e-mails from many of these less fortunate Americans. In their pleas, there's always dignity, but too often desperation. "Our school is closing in June of 2010, which means that I will be losing my job and my health insurance," writes Mary Dunn, a 58-year-old schoolteacher in Eden, S.D. "I am a Type I diabetic, and I had heart bypass surgery in 2005. My husband is also a teacher [here], so we will both be losing insurance. I am exploring options and have been told that I cannot stay on our group policy or transfer to another policy after our jobs cease because of my medical condition. What am I to do after 39 years of teaching to acquire adequate health coverage?" Dunn also serves as mayor of Eden, for which she is paid $45 a month with no health benefits.

Some years later, I decided the time was right to renew the quest for universal and affordable coverage. When I first introduced the bill in 1970, I didn't expect an easy victory (although I never suspected that it would take this long). I eventually came to believe that we'd have to give up on the ideal of a government-run, single-payer system if we wanted to get universal care. Some of my allies called me a sellout because I was willing to compromise. Even so, we almost had a plan that President Richard Nixon was willing to sign in 1974—but that chance was lost as the Watergate storm swept Washington and the country, and swept Nixon out of the White House. I tried to negotiate an agreement with President Carter but became frustrated when he decided that he'd rather take a piecemeal approach. I ran against Carter, a sitting president from my own party, in large part because of this disagreement. Health reform became central to my 1980 presidential campaign: I argued then that the issue wasn't just coverage but also out-of-control costs that would ultimately break both family and federal budgets, and increasingly burden the national economy. I even predicted, optimistically, that the business community, largely opposed to reform, would come around to supporting it.

At another Democratic convention, in arguing for this cause, I spoke of the insurance coverage senators and members of Congress provide for themselves. That was 1980. In the last year, I've often relied on that Congressional insurance. My wife, Vicki, and I have worried about many things, but not whether we could afford my care and treatment. Each time I've made a phone call or held a meeting about the health bill—or even when I've had the opportunity to get out for a sail along the Massachusetts coast—I've thought in an even more powerful way than before about what this will mean to others. And I am resolved to see to it this year that we create a system to ensure that someday, when there is a cure for the disease I now have, no American who needs it will be denied it.

Go to:http://www.newsweek.com/id/207406/page/1

In 1964, I was flying with several companions to the Massachusetts Democratic Convention when our small plane crashed and burned short of the runway. My friend and colleague in the Senate, Birch Bayh, risked his life to pull me from the wreckage. Our pilot, Edwin Zimny, and my administrative assistant, Ed Moss, didn't survive. With crushed vertebrae, broken ribs, and a collapsed lung, I spent months in New England Baptist Hospital in Boston. To prevent paralysis, I was strapped into a special bed that immobilizes a patient between two canvas slings. Nurses would regularly turn me over so my lungs didn't fill with fluid. I knew the care was expensive, but I didn't have to worry about that. I needed the care and I got it.

Now I face another medical challenge. Last year, I was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. Surgeons at Duke University Medical Center removed part of the tumor, and I had proton-beam radiation at Massachusetts General Hospital. I've undergone many rounds of chemotherapy and continue to receive treatment. Again, I have enjoyed the best medical care money (and a good insurance policy) can buy.

But quality care shouldn't depend on your financial resources, or the type of job you have, or the medical condition you face. Every American should be able to get the same treatment that U.S. senators are entitled to.

This is the cause of my life. It is a key reason that I defied my illness last summer to speak at the Democratic convention in Denver—to support Barack Obama, but also to make sure, as I said, "that we will break the old gridlock and guarantee that every American…will have decent, quality health care as a fundamental right and not just a privilege." For four decades I have carried this cause—from the floor of the United States Senate to every part of this country. It has never been merely a question of policy; it goes to the heart of my belief in a just society. Now the issue has more meaning for me—and more urgency—than ever before. But it's always been deeply personal, because the importance of health care has been a recurrent lesson throughout most of my 77 years.

Nothing I'm enduring now can compare to hearing that my children were seriously ill. In 1973, when I was first fighting in the Senate for universal coverage, we learned that my 12-year-old son Teddy had bone cancer. He had to have his right leg amputated above the knee. Even then, the pathology report showed that some of the cancer cells were very aggressive. There were only a few long-shot options to stop it from spreading further. I decided his best chance for survival was a clinical trial involving massive doses of chemotherapy. Every three weeks, at Children's Hospital Boston, he had to lie still for six hours while the fluid dripped into his arm. I remember watching and praying for him, all the while knowing how sick he would be for days afterward.

During those many hours at the hospital, I came to know other parents whose children had been stricken with the same deadly disease. We all hoped that our child's life would be saved by this experimental treatment. Because we were part of a clinical trial, none of us paid for it. Then the trial was declared a success and terminated before some patients had completed their treatments. That meant families had to have insurance to cover the rest or pay for them out of pocket. Our family had the necessary resources as well as excellent insurance coverage. But other heartbroken parents pleaded with the doctors: What chance does my child have if I can only afford half of the prescribed treatments? Or two thirds? I've sold everything. I've mortgaged as much as possible. No parent should suffer that torment. Not in this country. Not in the richest country in the world.

That experience with Teddy made it clear to me, as never before, that health care must be affordable and available for every mother or father who hears a sick child cry in the night and worries about the deductibles and copays if they go to the doctor. But that was just one medical crisis. My family, like every other, has faced many—at every stage of life. I think of my parents and the medical care they needed after their strokes. I think of my son Patrick, who suffered serious asthma as a child and sometimes had to be rushed to the hospital for treatment. (For this reason, we had no dogs in the house when Patrick was young.) I think of my daughter, Kara, diagnosed with lung cancer in 2002. Few doctors were willing to try an operation. One did—and after that surgery and arduous rounds of chemotherapy and radiation, she's alive and healthy today. My family has had the care it needed. Other families have not, simply because they could not afford it.

I have seen letters and e-mails from many of these less fortunate Americans. In their pleas, there's always dignity, but too often desperation. "Our school is closing in June of 2010, which means that I will be losing my job and my health insurance," writes Mary Dunn, a 58-year-old schoolteacher in Eden, S.D. "I am a Type I diabetic, and I had heart bypass surgery in 2005. My husband is also a teacher [here], so we will both be losing insurance. I am exploring options and have been told that I cannot stay on our group policy or transfer to another policy after our jobs cease because of my medical condition. What am I to do after 39 years of teaching to acquire adequate health coverage?" Dunn also serves as mayor of Eden, for which she is paid $45 a month with no health benefits.

How will we, as a nation, answer her? I've heard countless such stories, including one from the family of Cassandra Wilson, a 14-year-old who once was a competitive ice skater. She's uninsured because she has petit mal seizures, often 200 times a day. Her parents have run up $30,000 on their credit cards. They've sold her skating equipment on eBay to pay for her care.

These two cases represent only those patients who lack coverage. We also need to find answers for the increasing number of Americans whose insurance costs too much, covers too little, and can be too easily revoked when they face the most serious illnesses.

Our response to these challenges will define our character as a country. But the challenges themselves—and the demands for reform—are not new. In 1912, when Theodore Roosevelt ran for a third term as president, the platform of his newly created Progressive Party called for national health insurance. Harry Truman proposed it again more than 30 years after Roosevelt was defeated. The plan was attacked, not for the last time, as "socialized medicine," and members of Truman's White House staff were branded "followers of the Moscow party line."

For the next generation, no one ventured to tread where T.R. and Truman fell short. But in the early 1960s, a new young president was determined to take a first step—to free the elderly from the threat of medical poverty. John Kennedy called Medicare "one of the most important measures I have advocated." He understood the pain of injury and illness: as a senator, he had almost died after surgery to repair a back injury sustained during World War II, an injury that would plague him all of his life. I was in college as he recuperated and learned to walk without crutches at my parents' winter home in Florida. I visited often, and we spent afternoons painting landscapes and seascapes. (It was a competition: at dinner after we finished, we would ask family members to decide whose painting was better.) I saw how the pain would periodically hit him as we were painting; he'd have to put down his brush for a while. And I saw, too, how hard he fought as president to pass Medicare. It was a battle he didn't have the opportunity to finish. But I was in the Senate to vote for the Medicare bill before Lyndon Johnson signed it into law—with Harry Truman at his side. In the Senate, I viewed Medicare as a great achievement, but only a beginning. In 1966, I visited the Columbia Point Neighborhood Health Center in Boston; it was a pilot project providing health services to low-income families in the two-floor office of an apartment building. I saw mothers in rocking chairs, tending their children in a warm and welcoming setting. They told me this was the first time they could get basic care without spending hours on public transportation and in hospital waiting rooms. I authored legislation, which passed a few months later, establishing the network of community health centers that are all around America today.

Some years later, I decided the time was right to renew the quest for universal and affordable coverage. When I first introduced the bill in 1970, I didn't expect an easy victory (although I never suspected that it would take this long). I eventually came to believe that we'd have to give up on the ideal of a government-run, single-payer system if we wanted to get universal care. Some of my allies called me a sellout because I was willing to compromise. Even so, we almost had a plan that President Richard Nixon was willing to sign in 1974—but that chance was lost as the Watergate storm swept Washington and the country, and swept Nixon out of the White House. I tried to negotiate an agreement with President Carter but became frustrated when he decided that he'd rather take a piecemeal approach. I ran against Carter, a sitting president from my own party, in large part because of this disagreement. Health reform became central to my 1980 presidential campaign: I argued then that the issue wasn't just coverage but also out-of-control costs that would ultimately break both family and federal budgets, and increasingly burden the national economy. I even predicted, optimistically, that the business community, largely opposed to reform, would come around to supporting it.

That didn't happen as soon as I thought it would. When Bill Clinton returned to the issue in the first years of his presidency, I fought the battle in Congress. We lost to a virtually united front of corporations, insurance companies, and other interest groups. The Clinton proposal never even came to a vote. But we didn't just walk away and do nothing—even though Republicans were again in control of Congress. We returned to a step-by-step approach. With Sen. Nancy Landon Kassebaum of Kansas, the daughter of the 1936 Republican presidential nominee, I crafted a law to make health insurance more portable for those who change or lose jobs. It didn't do enough to fully guarantee that, but we made progress. I worked with my friend Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah, the Republican chair of our committee, to enact CHIP, the Children's Health Insurance Program; today it covers more than 7 million children from low-income families, although too many of them could soon lose coverage as impoverished state governments cut their contributions.

Incremental measures won't suffice anymore. We need to succeed where Teddy Roosevelt and all others since have failed. The conditions now are better than ever. In Barack Obama, we have a president who's announced that he's determined to sign a bill into law this fall. And much of the business community, which has suffered the economic cost of inaction, is helping to shape change, not lobbying against it. I know this because I've spent the past year, along with my staff, negotiating with business leaders, hospital administrators, and doctors. As soon as I left the hospital last summer, I was on the phone, and I've kept at it. Since the inauguration, the administration has been deeply involved in the process. So have my Senate colleagues—in particular Max Baucus, the chair of the Finance Committee, and my friend and partner in this mission, Chris Dodd. Even those most ardently opposed to reform in the past have been willing to make constructive gestures now.

To help finance a bill, the pharmaceutical industry has agreed to lower prices for seniors, not only saving them money for prescriptions but also saving the government tens of billions in Medicare payments over the next decade. Senator Baucus has agreed with hospitals on more than $100 billion in savings. We're working with Republicans to make this a bipartisan effort. Everyone won't be satisfied—and no one will get everything they want. But we need to come together, just as we've done in other great struggles—in World War II and the Cold War, in passing the great civil-rights laws of the 1960s, and in daring to send a man to the moon. If we don't get every provision right, we can adjust and improve the program next year or in the years to come. What we can't afford is to wait another generation.

I long ago learned that you have to be a realist as you pursue your ideals. But whatever the compromises, there are several elements that are essential to any health-reform plan worthy of the name.

First, we have to cover the uninsured. When President Clinton proposed his plan, 33 million Americans had no health insurance. Today the official number has reached 47 million, but the economic crisis will certainly push the total higher. Unless we act now, within a few years, 55 million Americans could be left without coverage even as the economy recovers.

All Americans should be required to have insurance. For those who can't afford the premiums, we can provide subsidies. We'll make it illegal to deny coverage due to preexisting conditions. We'll also prohibit the practice of charging women higher premiums than men, and the elderly far higher premiums than anyone else. The bill drafted by the Senate health committee will let children be covered by their parents' policy until the age of 26, since first jobs after high school or college often don't offer health benefits.

To accomplish all of this, we have to cut the costs of health care. For families who've seen health-insurance premiums more than double—from an average of less than $6,000 a year to nearly $13,000 since 1999—one of the most controversial features of reform is one of the most vital. It's been called the "public plan." Despite what its detractors allege, it's not "socialism." It could take a number of different forms. Our bill favors a "community health-insurance option." In short, this means that the federal government would negotiate rates—in keeping with local economic conditions—for a plan that would be offered alongside private insurance options. This will foster competition in pricing and services. It will be a safety net, giving Americans a place to go when they can't find or afford private insurance, and it's critical to holding costs down for everyone.

We also need to move from a system that rewards doctors for the sheer volume of tests and treatments they prescribe to one that rewards quality and positive outcomes. For example, in Medicare today, 18 percent of patients discharged from a hospital are readmitted within 30 days—at a cost of more than $15 billion in 2005. Most of these readmissions are unnecessary, but we don't reward hospitals and doctors for preventing them. By changing that, we'll save billions of dollars while improving the quality of care for patients.

Social justice is often the best economics. We can help disabled Americans who want to live in their homes instead of a nursing home. Simple things can make all the difference, like having the money to install handrails or have someone stop by and help every day. It's more humane and less costly—for the government and for families—than paying for institutionalized care. That's why we should give all Americans a tax deduction to set aside a small portion of their earnings each month to provide for long-term care.

Another cardinal principle of reform: we have to make certain that people can keep the coverage they already have. Millions of employers already provide health insurance for their employees. We shouldn't do anything to disturb this. On the contrary, we need to mandate employer responsibility: except for small businesses with fewer than 25 employees, every company should have to cover its workers or pay into a system that will.

We need to prevent disease and not just cure it. (Today 80 percent of health spending pays for care for the 20 percent of Americans with chronic illnesses like diabetes, cancer, or heart disease.) Too many people get to the doctor too seldom or too late—or know too little about how to stay healthy. No one knows better than I do that when it comes to advanced, highly specialized treatments, America can boast the best health care in the world—at least for those who can afford it. But we still have to modernize a system that doesn't always provide the basics.

I've heard the critics complain about the costs of change. I'm confident that at the end of the process, the change will be paid for—fairly, responsibly, and without adding to the federal deficit. It doesn't make sense to negotiate in the pages of NEWSWEEK, but I will say that I'm open to many options, including a surtax on the wealthy, as long as it meets the principle laid down by President Obama: that there will be no tax increases on anyone making less than $250,000 a year. What I haven't heard the critics discuss is the cost of inaction. If we don't reform the system, if we leave things as they are, health-care inflation will cost far more over the next decade than health-care reform. We will pay far more for far less—with millions more Americans uninsured or underinsured.

This would threaten not just the health of Americans but also the strength of the American economy. Health-care spending already accounts for 17 percent of our entire domestic product. In other advanced nations, where the figure is around 10 percent, everyone has insurance and health outcomes that are equal or better than ours. This disparity undermines our ability to compete and succeed in the global economy. General Motors spends more per vehicle on health care than on steel.

We will bring health-care reform to the Senate and House floors soon, and there will be a vote. A century-long struggle will reach its climax. We're almost there. In the meantime, I will continue what I've been doing—making calls, urging progress. I've had dinner twice recently at my home in Hyannis Port with Senator Dodd, and when President Obama called me during his Rome trip after meeting with the Pope, much of our discussion was about health care. I believe the bill will pass, and we will end the disgrace of America as the only major industrialized nation in the world that doesn't guarantee health care for all of its people.

At another Democratic convention, in arguing for this cause, I spoke of the insurance coverage senators and members of Congress provide for themselves. That was 1980. In the last year, I've often relied on that Congressional insurance. My wife, Vicki, and I have worried about many things, but not whether we could afford my care and treatment. Each time I've made a phone call or held a meeting about the health bill—or even when I've had the opportunity to get out for a sail along the Massachusetts coast—I've thought in an even more powerful way than before about what this will mean to others. And I am resolved to see to it this year that we create a system to ensure that someday, when there is a cure for the disease I now have, no American who needs it will be denied it.

Go to:

Kennedy's absent voice on health bill resonates

Kennedy's absent voice on health bill resonates

July 16, 2009

July 16, 2009

As a divided Senate tangles over health care legislation, there is bipartisan consensus on one point: Ted Kennedy could make a big difference, if only he were here.

“He would lend a gravitas to the issue that we’re kind of missing right now,” said Senator Tom Harkin, Democrat of Iowa and a member of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee.

Mr. Harkin’s Republican counterparts similarly invoked Mr. Kennedy in criticizing a health care measure the committee approved Wednesday with only Democratic support.

“It is a very one-sided, very liberal bill,” said Senator Orrin G. Hatch of Utah. “I know that Ted would not have done that had he been able to be here.”

Senator Edward M. Kennedy, who is battling brain cancer, has not been on Capitol Hill since April.

Colleagues routinely lament his absence, which has been especially painful to Mr. Kennedy, the committee chairman, who has spent much of his career trying to expand health coverage.

People close to Mr. Kennedy marvel at how his fight for his life could coincide so dramatically with what may be the culminating summer of his life’s cause. “It’s been a miraculous story,” said Senator Christopher J. Dodd, Democrat of Connecticut.

The 77-year-old Mr. Kennedy is at his home on Cape Cod, undergoing new chemotherapy treatments that have left him depleted and frustrated in recent weeks, friends say.

“He has moments that are tremendous,” Mr. Dodd said. “And others that are really tough.”

Ever since Mr. Kennedy’s diagnosis in May 2008, friends and others have tried to honor an unspoken code not to talk about his health except to say that he is doing well, engaged in his work from afar and looking forward to returning to the Senate.

Colleagues and public officials have also been wary of appearing to be planning for life after Mr. Kennedy — a particularly verboten topic in Massachusetts, where several Democratic members of Congress and possibly members of the Kennedy family could vie for the first Senate seat to come open in that state since John Kerry, the junior senator, was elected in 1984.

Mr. Kennedy’s office says the senator is in touch with his staff and monitoring the progress of health care legislation by phone and C-Span.

“He’s doing well, continuing to balance his treatment with his work,” said Mr. Kennedy’s spokeswoman, Melissa Wagoner.

But conversations with friends and colleagues about Mr. Kennedy’s condition now typically include a weary acceptance of the inevitable: that his cancer — whose survival time for people similarly afflicted is typically measured in months, not years, from diagnosis — is taking a mounting toll.

The “constant phone calls” that his staff and fellow senators reported over the winter have fallen off; people who have seen him say Mr. Kennedy comprehends things well but struggles to speak at times.

Vicki Kennedy, Mr. Kennedy’s wife, has limited visitors on Cape Cod to a few friends and family members. She does not want her husband to be seen in his weakened state, friends say; nor does she want him to expend limited energy.

On days when he feels strong enough, Mr. Kennedy will go out on his sailboat (a video clip last week showed him bundled up in a red parka as he arrived at the pier) or take a golf cart drive to visit his older sister, Eunice Shriver, who lives up the street in Hyannis Port.

Last week, a family member said, Mr. Kennedy and his sister toasted her 88th birthday together while overlooking the ocean.

When President Obama met with Pope Benedict XVI at the Vatican last Friday, he asked the pontiff to pray for Mr. Kennedy, said Robert Gibbs, the White House spokesman. Mr. Obama also delivered a private letter from the senator to the pope.

As his health has declined, Mr. Kennedy has become more of an inspirational leader than a tangible one.

He turned over his day-to-day committee duties to Mr. Dodd in the spring.

Mr. Dodd called him Tuesday night to tell him the health committee, known as HELP, would pass the health bill — whose centerpiece is a government-run insurance plan — the next day.

“I called about 8:15, and he was already asleep,” Mr. Dodd said. Mr. Kennedy called back at 7 a.m. Wednesday sounding thrilled.

“Just bellowing with joy,” Mr. Dodd said, “as excited as I’ve heard him in a long time.”

Mr. Dodd takes exception to Republican criticism that the committee’s bill would have been less partisan under Mr. Kennedy, saying Mr. Kennedy would have fought for its major components.

But he also said the Republicans might drop their opposition as the legislation evolved. “I don’t take that as a permanent problem,” he said, “and Teddy wouldn’t either.”

Senators of both parties say the health care debate is entering its most acute phase — with multiple committees in the House and Senate trying to forge compromises — a period Mr. Harkin called “Kennedy time.”

No one, he said, is better suited than Mr. Kennedy to navigating the obstacles that could derail, or delay, the passage of a health care bill.

“Let me say something that’s very obvious,” said Senator Charles E. Grassley of Iowa, the ranking Republican on the Senate Finance Committee. “If Kennedy were here, it would make melding the Finance Committee bill and the HELP Committee bill much easier.”

Similarly, members of the health committee, particularly Democrats, often speak in terms of “What would Teddy do?” Senator Patty Murray, Democrat of Washington, said. “We’re all working to do what we think he’d want us to do.”

Aside from Mr. Obama’s determination to deliver comprehensive health care legislation, Mr. Kennedy’s precarious health has created an unspoken urgency.

“We are conscious that it would be appropriate that he should be chairman of this committee when the bill is passed,” said Senator Jack Reed, Democrat of Rhode Island and a member of the health committee.

Some hold out hope that Mr. Kennedy can make a last-ditch appeal to his Republican friends — a kind of dying wish — to support the legislation so he can complete his life’s work.

It is not clear, though, that such a request would have the desired effect.

Mr. Hatch, a close friend of Mr. Kennedy, said, “I would like to work with him on it and have a legacy issue for him.”

But he said that that would have been more likely if Mr. Kennedy had been more involved in shaping the bill. Mr. Hatch said he had not spoken with Mr. Kennedy in several weeks.

“I’m a believer in miracles,” Mr. Hatch said. “I’m praying that somehow or other he’ll come through. But it’s very dramatically against him."

I'm sure Ted is fighting like a lion! He had the courage to face up to the journalist with pride, like the photo where he's facing the photograph. Ted, you're the best!

Friday, July 3, 2009

Kennedy/Shriver clan grows

Anthony Kennedy Shriver and wife Alina have welcomed a fifth child, John Joseph Sargent Shriver, into their large Miami family this week.

“I am so blessed and grateful for my family to welcome our new son into this world,” the Best Buddies International founder told People.com.

“Women are miracle workers,” he said of his 44-year-old wife.

Baby John weighed in at 7 pounds, 9 ounces and is 20.5 inches long.

The other Shriver kids are Teddy, 20, Eunice, 15, Francesca, 14, and Carolina, 8.

“Why did we decide to have another?” Shriver nephew of late President John F. Kennedy quipped to People. “Well, you could say we have an active sex life!”

Go to:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)