Senator Edward M. Kennedy, who carried aloft the torch of a Massachusetts dynasty and a liberal ideology to the citadel of Senate power, but whose personal and political failings may have prevented him from realizing the ultimate prize of the presidency, died late Tuesday night. The senator was 77.

Overcoming a history of family tragedy, including the assassinations of a brother who was president and another who sought the presidency, Senator Kennedy seized the role of being a “Senate man.’’ He became a Democratic titan of Washington who fought for the less fortunate, who crafted unlikely deals with conservative Republicans, and who ceaselessly sought support for universal health coverage.

“Teddy,’’ as he was known to intimates, constituents, and even his fiercest enemies, was an unwavering symbol to the left and the right - the former for his unapologetic embrace of liberalism, and latter for his value as a political target. But with his fiery rhetoric, his distinctive Massachusetts accent, and his role as representative of one of the nation’s best-known political families, he was widely recognized as an American original. In the end, some of those who might have been his harshest political enemies, including former President George W. Bush, found ways to collaborate with the man who was called the “last lion’’ of the Senate.

Senator Kennedy’s White House aspirations may have been undercut by his actions on the night he drove off a bridge at Chappaquiddick Island and failed to promptly report the accident in which Mary Jo Kopechne, who had worked for his brother Robert, died. When Kennedy nonetheless later sought to wrest the presidential nomination from an incumbent Democrat, Jimmy Carter, he failed. But that failure prompted him to reevaluate his place in history, and he dedicated himself to fulfilling his political agenda by other means, famously saying, “the dream shall never die.’’

Those causes endure today and remain at the forefront of the American political stage, evidenced most recently by the fight for universal health care.

He was the youngest child of a famous family, but his legacy derived from quiet subcommittee meetings, conference reports, and markup sessions. The result of his efforts meant hospital care for a grandmother, a federal loan for a working college student, or a better wage for a dishwasher.

With a family saga that blended Greek tragedy and soap opera, the Kennedys fascinated America and the world for half a century. “I have every expectation of living a long and worthwhile life,’’ Senator Kennedy said in 1994. Such an expectation contrasted with the fate of his brothers.

Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. was killed in 1944 on a World War II bombing mission. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. Senator Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated while campaigning for president in Los Angeles in 1968.

Ted Kennedy’s congressional career was remarkable not only for its accomplishments, but for its length of 47 years. Massachusetts voters installed him in the Senate nine times - starting with a special election in 1962.

Since the doors of the Senate first opened in 1789, only Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia and the late Strom Thurmond of South Carolina served longer.

Senator Kennedy brought to the Senate a trait his brothers lacked - patience - and what his mother called a “ninth-child talent,’’ a blend of toughness and tact.

Birth of a political legend The ninth child of Joseph P. and Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy was born on the 200th anniversary of George Washington’s birth, Feb. 22, 1932. His brother Jack, then at the Choate School in Connecticut, wrote to his parents, asking to be godfather and urging the new arrival to be baptized George Washington Kennedy.

The parents agreed to the first request but named the child Edward Moore Kennedy, after one of his father’s assistants. Part of his boyhood was spent in London, where his father was US ambassador to Great Britain.

After nine schools on two continents, he entered Milton Academy in 1946, joined the drama club and the debating society, played tennis and football, and maintained mostly midlevel grades, including in Spanish, a subject that would trouble him at Harvard College, where, in 1951, he asked a friend to take a Spanish exam for him.

A proctor recognized the substitute, and both students were expelled but were told they could return to Harvard if they showed evidence of “constructive and responsible citizenship.’’

The incident would become the first of several episodes creating public doubts about his character. The Spanish exam resurfaced in 1962, when some Harvard professors opposed his nomination for the US Senate. President Kennedy negotiated the release of expulsion details to the Globe, and Ted Kennedy’s confession diminished its political impact.

After the Harvard expulsion, he volunteered for the military, and Private Kennedy met a more diverse group of people at Fort Dix, N.J., than he would have in Cambridge. His father helped arrange an assignment, during fighting in Korea, to NATO headquarters in Paris.

In 1954, after two years in the Army, Ted Kennedy returned to Harvard, became a resident of Winthrop House, as were his brothers, and an end on the football team, for which he scored a touchdown in a losing effort against Yale.

He graduated from Harvard in 1956 and the University of Virginia Law School three years later.

At a Kennedy family event at Manhattanville College, the alma mater of his sisters, he met Joan Bennett, the daughter of a New York advertising executive. They married in 1958, the same year he managed the Senate reelection campaign of his brother John against Vincent J. Celeste of East Boston. The outcome was not in doubt; Ted’s assignment was to steer the incumbent to a victory big enough to impress national Democratic Party bosses. The victory margin was 857,000, the highest in the Commonwealth’s history.

In 1959, Ted Kennedy headed west to help his brother’s presidential campaign. At the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles in 1960, when Wyoming cinched JFK’s nomination, Ted Kennedy stood among the state’s delegates, cheering them. During the 1960 election against Republican Richard Nixon, Ted Kennedy considered moving from Massachusetts if JFK lost the White House. Instead, his brother’s win intertwined the destinies of Edward Moore Kennedy and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

On to the Senate John F. Kennedy declared in his inaugural address that “the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans.’’ This iconography would play out over generations of Kennedys.

Upon winning the presidency, John Kennedy persuaded Governor Foster Furcolo to fill his vacant Senate seat by appointing Benjamin A. Smith II, the mayor of Gloucester who was a friend of the president at Harvard.

On March 14, 1962, after he attained the constitutional age of 30 to be eligible for election to the Senate, Edward Kennedy announced his candidacy for the unexpired term of his brother. His only public experience was a year as assistant district attorney of Suffolk County, and he had to take on two Massachusetts dynasties.

In the special election, he first faced state Attorney General Edward J. McCormack Jr., the nephew of US House Speaker John W. McCormack.

On several issues, including nuclear weapons and civil liberties, McCormack was more liberal than his opponent, but the campaign was not ideological.

At a debate in South Boston, McCormack ridiculed the young Ted, saying the senatorial job “should be merited, not inherited.’’ Pointing his finger at his opponent, he said: “If his name were Edward Moore, with his qualifications - with your qualifications, Teddy - if it was Edward Moore, your candidacy would be a joke.’’

Ted Kennedy looked pained and shocked. His silence created a wave of sympathy.

“Some say Eddie came on too strong, others still say he was right on the mark; I agree with both of them,’’ Senator Kennedy said at McCormack’s funeral 35 years later.

Ted Kennedy went on to win 69 percent of the primary vote and then to defeat George C. Lodge, the son of the former Republican senator, in the general election. After his November victory, he was sworn in swiftly, to gain more senatorial seniority. He took the oath from Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson on Nov. 7, 1962.

Even with a brother in the White House and another as attorney general, a freshman senator was supposed to work diligently for local concerns and to perform committee work in patient obscurity. Senator Kennedy did so, taking on his brother’s legislative concerns on refugees and immigrants. He sought “more for Massachusetts’’ by pursuing fishery development and a Cambridge electronics research center for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Disasters strike On Nov. 22, 1963, Senator Kennedy was presiding over the chamber, a chore assigned to freshman members, when a messenger arrived at the rostrum with the news from Dallas. After confirming with the White House the president’s assassination, Senator Kennedy and his sister, Eunice, flew to Hyannis Port to deliver the news to their father. Joseph P. Kennedy had suffered a stroke in 1961 and could not speak or walk.

The senator called the new president that night. “I want you to know how much I appreciate your thoughts for my mother and family,’’ he said. Johnson maintained more cordial relations with the youngest Kennedy than with his siblings, Robert in particular.

In Congress, Senator Kennedy did not deliver his first major address from the floor until April 1964. The subject was civil rights, the unfinished business of his slain brother.

Eager to win a full six-year term later that year, Senator Kennedy planned to visit Springfield to accept the endorsement of the Democratic state convention. On the night of June 19, after casting votes on final passage of a civil rights bill, Senator Kennedy and the convention’s keynote speaker, Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana, boarded a twin-engine private plane en route to Barnes Municipal Airport in Westfield.

In heavy fog, the aircraft crashed in an apple orchard, killing the pilot and a Kennedy aide. Senator Kennedy sustained three broken vertebrae, fractured ribs, a punctured lung, a bruised kidney, and internal hemorrhaging.

During a visit to the hospital, Robert Kennedy muttered mordantly, “I guess the reason my mother and father had so many children is so that some would survive.’’

Political chores were left to Joan, who shuttled between campaign events and hospital visits. After a six-month recuperation, Senator Kennedy was released, but back injuries would cause him pain for the rest of his life. The Republican opponent was Howard Whitmore, the former mayor of Newton, who said, “My opponent is flat on his back, and, from a gentleman’s standpoint, I can’t campaign against that.’’ Senator Kennedy was reelected with 74.3 percent of the vote.

In that same election, voters of New York elected Robert F. Kennedy as their senator. In 1965, on the first day of the 89th Congress, the Kennedy brothers were sworn in together.

The siblings teased each other frequently but seldom diverged in their liberal voting patterns. Robert had seniority in the family and was a former US attorney general, but Edward took the lead on legal issues such as repealing the poll tax.

Oceanography, historic preservation, immigration, voting rights - these issues also occupied the junior senator from Massachusetts in 1965. But he made more news by sponsoring the nomination of Boston Municipal Court Judge Francis X. Morrissey, a friend of the family, for a seat on the federal district court.

Undaunted by the opposition of the American Bar Association, Senator Kennedy sent Morrissey’s name to the White House, and President Johnson nominated him. The hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee were stormy, with the Senate minority leader, Everett M. Dirksen of Illinois, mocking Morrissey’s credentials and with ABA officials calling him unqualified.

Republicans found ammunition in stories in the Globe disputing Morrissey’s assertions that he attended law school at Boston College and Southern Law School in Athens, Ga. Senator Kennedy’s vote-counting abilities led him to withdraw his friend’s name.

In October 1965, the senator made his first visit to South Vietnam, a nation that would profoundly affect the United States, President Johnson, and the Kennedys.

The longest war in American history fulfilled a promise inherent in JFK’s inaugural speech in 1961 that “we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and success of liberty.’’

By 1967, antiwar marches and rallies were proliferating and on Nov. 30 Senator Eugene J. McCarthy of Minnesota agreed, after Robert Kennedy declined, to challenge Johnson in the 1968 Democratic primaries. After McCarthy won 42 percent of the New Hampshire vote and before Johnson would bow out, Robert Kennedy reconsidered and entered the contest.

In June, after winning the California primary, Robert Kennedy was assassinated. At St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, the voice of the surviving Kennedy brother cracked as he eulogized Robert as “a good and decent man, who . . . saw war and tried to stop it.’’ Senator Kennedy became the surrogate father of his brothers’ children and a patriarch of the growing clan.

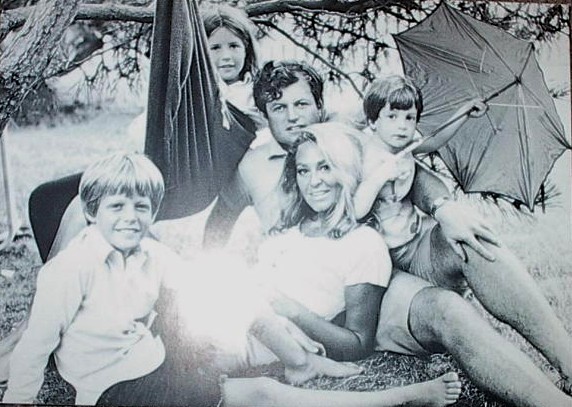

His own family had grown with the birth of Patrick Joseph Kennedy a year before. Kara Anne had been born in 1960 and Edward Jr. in 1961. In addition to his children and his wife, Vicki, Senator Kennedy leaves two stepchildren, Caroline and Curran Raclin, his sister, Jean Kennedy Smith, and four grandchildren.

Vietnam dominated the 1968 Democratic National Convention, as did speculation about Senator Kennedy’s intentions. “Like my brothers before me, I pick up a fallen standard,’’ he said at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester a few weeks before the convention. “Sustained by the memory of our priceless years together, I shall try to carry forward that special commitment to jus tice, to excellence, and to the courage that distinguished their lives.’’

But the Capitol, not the White House, seemed the focus of his intentions. The senator said he would not run for president or vice president. After Richard Nixon defeated Hubert H. Humphrey in a close contest, Senator Kennedy surprised many in Washington by running for majority whip. By a 31-26 vote, he defeated the incumbent, another son of a famous political dynasty, Senator Russell B. Long of Louisiana.

On a cold January night, before celebrating at his home in McLean, Va., the 36-year-old senator drove to Arlington National Cemetery, where the gravesite of Robert was under construction, next to John’s.

Tragedy and turmoil Majority leader Mike Mansfield of Montana welcomed his new assistant, saying, “Of all the Kennedys, the senator is the only one who was and is a real Senate man.’’ Senator Kennedy mobilized Democrats against what he called the “folly’’ of an antiballistic missile system proposed by President Nixon and continued to oppose the war in Vietnam. On July 18, 1969, Mansfield predicted that his colleague would not run for president in 1972, saying “He’s in no hurry. He’s young. He likes the Senate.’’

On that same day, Senator Kennedy arrived on an island that his actions would make notorious. On Chappaquiddick, across a narrow inlet from Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard, six young women who had worked on Robert Kennedy’s campaign gathered for a reunion at a rented cottage. Senator Kennedy’s marriage was already troubled, and he had been seen in the company of other glamorous women. But the women at Chappaquiddick were all serious, professional political operatives.

Mary Jo Kopechne, 28, had worked for RFK’s Senate office. A passenger in a car driven by Ted Kennedy, she drowned after the car skidded off a bridge. Senator Kennedy failed to report the accident for 10 hours. The crash gave him a minor concussion and a major personal and political crisis.

As American astronauts walked on the moon, fulfilling a JFK pledge, Chappaquiddick was front-page news across the globe. The senator was unable to explain the accident for days. After consulting in Hyannis Port with his brothers’ advisers and speechwriters, he gave a televised speech a week later. He praised Kopechne and attacked “ugly speculation about her character,’’ wondered aloud “whether some awful curse did actually hang over the Kennedys,’’ then asked Massachusetts voters whether he should resign. They replied overwhelmingly: No.

His critics snarled that Senator Kennedy “got away with it’’ at Chappaquiddick, but the price he paid in personal grief was as high as the cost in presidential politics. During the Cold War, voters expected quick and cool judgment from presidents. Senator Kennedy, in effect, disqualified himself when he confessed on television that he should have alerted police immediately: “I was overcome, I’m frank to say, by a jumble of emotions: grief, fear, doubt, exhaustion, panic, confusion, and shock.’’

He returned to his work in the Senate and in December 1969 began a long campaign “to move now to establish a comprehensive national health care insurance program.’’ He also led the effort to give 18-year-olds the right to vote.

After winning reelection in 1970 with 62 percent of the vote, he found how Chappaquiddick reverberated in the Senate chamber. In January 1971, Senator Byrd unseated Senator Kennedy as majority whip by a 31-24 vote of the Democratic caucus.

Senator Kennedy privately thanked Byrd years later because the loss made him concentrate on committee work in health care, refugees, civil rights, the judiciary, and foreign policy, areas in which he would leave a lasting imprint.

Also in 1971, he made one of his strongest statements on Northern Ireland amid an explosion of political violence, saying “Ulster is becoming Britain’s Vietnam,’’ which the British prime minister called an “ignorant outburst.’’ Years later, on St. Patrick’s Day in 1977, Senator Kennedy and other leaders would ask Irish-Americans to shun the violence of the Irish Republican Army. It was called “the big four’’ statement, after Senator Kennedy and Speaker Thomas P. O’Neill Jr. of Massachusetts, and Governor Hugh L. Carey and Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York.

As he was rebuilding his stature in the chamber in the fall of 1973, Senator Kennedy and his wife, Joan, received devastating news. Their 12-year-old son, Edward Jr., had cancer and his leg had to be amputated. Although Ted Jr. overcame the cancer, the crisis cooled the senator’s ambitions about running for president in 1976.

Hometown political issues also took a toll. In Boston, crowds vehemently protested a school desegregation busing order by a family friend, federal Judge W. Arthur Garrity. The issue dogged Senator Kennedy throughout 1974 and 1975. In 1976, although challenged in the Democratic primary by two antibusing candidates, he won with 74 percent and in November chalked up a reelection victory tally of 69 percent.

The run for the White House The election of 1976 would bring a Democrat back into the White House. Jimmy Carter of Georgia, however, was not a Kennedy Democrat. The ideological divide between the two was profound. Even though the Massachusetts senator had pursued some pro-business policies such as deregulating airlines, he believed in an active government that some would call intrusive; Carter tended to be more conservative. Senator Kennedy thought Carter’s health care programs were timid. The president sometimes resented Senator Kennedy’s celebrity status, especially when foreign leaders consulted with the senator.

The divisions only widened over Carter’s first term. When the Democrats held a mid-term conference in Memphis in December 1978, it was dominated by the senator’s nautical metaphor. “Sometimes a party must sail against the wind,’’ he said. “We cannot afford to drift or lie at anchor. We cannot heed the call of those who say it is time to furl the sail.’’ Carter’s response to a group of Democratic congressmen: If Senator Kennedy did challenge him in the next election, “I’ll whip his ass.’’

Shortly before he announced that challenge, however, Senator Kennedy stumbled in an interview with CBS’s Roger Mudd. The commentator’s question seemed simple: Why was he running for president.

“Well, I’m - were I to make the announcement and to run,’’ Senator Kennedy said, “the reasons that I would run is because I have a great belief in this country. That it is - there’s more natural resources than any nation in the world; the greatest education population in the world; the greatest technology of any country in the world; the greatest capacity for innovation in the world; and the greatest political system in the world.’’

His responses to questions about Chappaquiddick sounded rehearsed, and the interview was widely considered a disaster. He would not recover.

On Nov. 7, 1979, three days after the interview was broadcast, the 47-year-old senator formally declared his candidacy for the 1980 Democratic presidential nomination, saying he was “compelled by events and by my commitment to public life.’’

“For many months, we have been sinking into crisis. Yet we hear no clear summons from the center of power,’’ he said, standing on the stage of Faneuil Hall before a giant painting of Daniel Webster, a longtime US senator from Massachusetts who never became president.

Unable to persuade Democrats to abandon a Democratic president, Senator Kennedy won only 10 of the 35 presidential primaries. In August, he reluctantly endorsed Carter at the Democratic National Convention in New York and offered his own anthem to the Democratic Party. He cited Jefferson, Jackson, Franklin Roosevelt, and those he had met at “the closed factories and the stalled assembly lines.’’ After congratulating Carter, he said, “For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die.’’

The lion of the Senate In 1981, because of Ronald Reagan’s coattails, Senator Kennedy was in the Senate minority for the first time. But he was accustomed to reaching across the aisle for support. Throughout his career, Senator Kennedy’s name animated Republican fund-raising efforts. In reality, the GOP’s bete noire cooperated with party leaders from Barry Goldwater to John McCain, a list that included conservative stalwarts Robert Dole, Orrin Hatch, and Alan Simpson.

Senator Kennedy’s success owed more to craftsmanship than charm, more to diligence than blarney. In 1985, outside the hearing room of the Armed Service Committee, a reporter encountered Senator John Warner, a Republican of Virginia, who spontaneously volunteered praise of his liberal colleague from Massachusetts: “This man works as hard as anyone. When he knows his subject, he really knows it. He listens, he learns, and he’s an asset to this committee.’’

In the 1960s, the young senator had learned a lesson from Senator Philip Hart of Michigan, who said of the Senate, “you measure accomplishments not by climbing mountains, but by climbing molehills.’’

In the 1980s, those molehills amounted to the renewal of the Voting Rights Act; an overhaul of federal job training (co-sponsored by a freshman senator from Indiana, Dan Quayle); and, with his Massachusetts colleagues from the House, Speaker O’Neill and Representative Edward P. Boland, a steady assault on Reagan administration policies in Central America.

In 1985, Senator Kennedy renounced presidential ambitions, saying to Bay State voters, “I will run for reelection to the Senate. I know that this decision means that I may never be president. But the pursuit of the presidency is not my life. Public service is.’’

“When he finally lifted the curse from himself that Kennedys had to be president, he truly became a legislator,’’ said Simpson, a Wyoming Republican who served 18 years in the Senate with Kennedy. “In fact, he immersed himself in legislation.’’

Others in the Kennedy clan would join him in such efforts.

In 1986, he watched with pride as his nephew Joseph won the seat vacated by O’Neill and in 1994 as his son, Patrick, won a congressional seat from Rhode Island.

Not all family matters, however, were a source of pride. In 1991, the senator had to testify in Palm Beach about rape charges brought against his nephew William Kennedy Smith in the aftermath of a drinking party organized by Senator Kennedy. The incident embarrassed the senator into silence during judiciary committee hearings into allegations of sexist conduct against Clarence Thomas, later confirmed as a Supreme Court justice.

Senator Kennedy’s behavior continued to provide fodder to gossip sheets. His reputation as a roustabout lingered until, years after he and Joan divorced in 1982, Senator Kennedy met Victoria Reggie, a Washington lawyer and divorced mother of two who was 22 years younger than the senator. They wed in 1992 and began a partnership that brought equilibrium and focus to his life.

In 1994, when Republicans recaptured the House for the first time in 40 years, no Democrat was safe, even the leading lion of liberalism in Massachusetts. A Republican businessman, Mitt Romney, captured the attention of some Bay Staters until, in a Faneuil Hall debate, Senator Kennedy proved his mastery of the issues.

For the senator, it was a relatively close call. He won with 58 percent of the vote, his smallest margin since his first election in 1962.

Senator Kennedy returned to form in subsequent reelections, winning by lopsided margins in 2000 and 2006 over lesser Republican competitors.

In Washington, he continued to work on issues subtle and unsubtle. In the latter category was one of his favorites, raising the minimum wage, a perennial struggle because its recipients lacked the Washington lobbies that support business interests.

As he had done for more than half his time in Washington, Senator Kennedy launched his crusade on behalf of those who daily do the menial work that make everyone else’s day cleaner, brighter, and safer. “The minimum wage,’’ he often said, “was one of the first and is still one of the best antipoverty programs we have.’’

During the administration of Republican George W. Bush, Senator Kennedy led the Senate’s antiwar faction as the president pressed Congress for the authorization to use military force against Iraq.

In a speech at Johns Hopkins University about a year after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Senator Kennedy said the administration had failed to make the case for a preemptive attack.

“I do not accept the idea that trying other alternatives is either futile or perilous, that the risks of waiting are greater than the risk of war,’’ Senator Kennedy said, recalling his brother’s restraint in dealing with the Soviet Union during the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962.

Two weeks later, the House and Senate passed the Iraq war resolution by wide margins. Senator Kennedy was among 21 Democrats who voted in opposition.

But Senator Kennedy displayed a willingness to be helpful when he thought Bush was right. He was a force behind the Bush administration’s chief domestic policy achievement in its first term, No Child Left Behind, the sweeping education bill that mandated testing to measure student progress. Senator Kennedy was a lead author and attended the signing ceremony in February 2002.

When Bush introduced him, the president said: “He is a fabulous United States senator. When he’s against you, it’s tough. When he’s with you, it is a great experience.’’

In early 2008, shortly before his cancer diagnosis, Senator Kennedy surprised much of the political world by endorsing Senator Barack Obama for president over Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton. The endorsement was seen as a passing of the Kennedy torch to the man aspiring to be the nation’s first black president.

With less than two weeks before Obama would face the far better-known Clinton in ’’Super Tuesday’’ contests in about half the states of the country, Senator Kennedy’s endorsement came at an optimal moment. Obama held Clinton to a draw in those contests, setting him up for his nomination and election as president.

Though Obama lost the Massachusetts primary to Clinton in what some saw as a sign of Senator Kennedy’s declining influence many analysts believed that Senator Kennedy’s support helped spur Obama to major victories in states where delegates were chosen in caucuses of party activists, many of whom had decades of allegiance to the longtime senator.

Despite his illness, Senator Kennedy made a forceful appearance at the Democratic convention in Denver, exhorting his party to victory and declaring that the fight for universal health insurance had been “the cause of my life.’’

He pursued that cause vigorously, and even as his health declined, he spent days reaching out to colleagues to win support for a sweeping overhaul; when members of Obama’s administration questioned the president’s decision to spend so much political capital on the seemingly intractable health care issue, Obama reportedly replied, “I promised Teddy.’’

Go to:

http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2009/08/26/kennedy_dead_at_77/

FEEL FREE TO LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS AFTER READING THE MOST RECENT KENNEDY NEWS!!!

Monday, August 31, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment