Even though he had just lost a key vote in the Senate on a cherished piece of legislation — the patients' bill of rights — there was a lightness to Senator Edward M. Kennedy's step as he strode out of the Capitol on a Thursday night in mid-July of 1999.

For one thing, he knew the legislative battle was not over. "We'll be back to fight and fight and fight again," Kennedy vowed. But what really buoyed the senator's spirits was the prospect of the wedding that weekend of his niece, Rory, the youngest child of his brother Bobby, at the family compound in Hyannis Port. Rory had been born six months after her father was assassinated in June 1968 — a turning point in Ted Kennedy's life, the moment when, though only 36, he was thrust into the role of family patriarch.

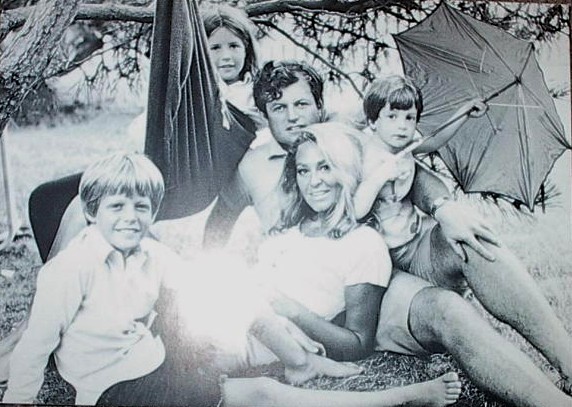

The wedding promised to be the kind of family event that Kennedy absolutely reveled in, and as he walked down the Capitol steps, he talked animatedly about how much he was looking forward to it. He knew the compound would fill up with the two dozen nieces and nephews to whom he was affectionately known as "the Grand Fromage" — French for "the big cheese." He had been a surrogate dad through much of their youth, taking them on camping trips to the Berkshires, bringing them to Civil War battlefields, teaching them to sail, beaming up at them from the pew at their First Communions.

"He's more than an uncle to his nieces and nephews," says Caroline Kennedy, the daughter of President John F. Kennedy. "I just feel so lucky to have the connection to my father and my whole family history."

On those trips, Kennedy made sure to carve out time to take the youngsters, singly or in pairs, for walks in the woods or strolls on the beach. Though the ostensible purpose was to steep the children in an appreciation of history and nature, Kennedy was also intent on sending a message: We are an unbreakable unit.

"Those kids, he was the father to all of them," says Don Dowd, a friend who drove the clan on those outings. "They all relied on him: John's kids, and Bobby's, and his own."

But there was another, sadder duty for which the Kennedy family had come to rely on him. When there is a family crisis, notes Caroline, "He's the first person who calls, the first person who shows up." And it was that grim duty — rather than singing, dancing, and toasting at Rory's wedding — that Ted Kennedy would have to shoulder, once again, that summer weekend in 1999. And it was Caroline in particular who would need Kennedy's support.

On the night of Friday, July 16, setting in motion a drama that would rivet the nation and crack the heart of anyone old enough to remember a little boy's salute, a single-engine Piper Saratoga piloted by John F. Kennedy Jr. plunged into the ocean off Martha's Vineyard. It would be four days before the bodies of John Jr., 38, along with his wife, 33-year-old Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, and her 34-year-old sister, Lauren Bessette, would be found.

The senator had arrived in Hyannis Port earlier on Friday. A festive air surrounded the wedding preparations, with a large white tent on the lawn for the nearly 300 invited guests. Late that night, Kennedy was awakened with the news that John Jr.'s plane was overdue. Kennedy anxiously placed a call to John's apartment in the TriBeCa neighborhood of New York City. A friend who was staying in the apartment answered the phone. Kennedy asked him whether, perhaps, John's plane had not left. The friend told Kennedy that it had.

Around 2 a.m., a family friend telephoned the Coast Guard at Woods Hole to report a missing plane. By early morning, a rescue mission was in full swing and a heartsick Ted Kennedy had to step into a role with which he was all too familiar. Caroline was not there — she was on a rafting vacation in Idaho with her husband and three children — but the senator did his best to console other family members.

On Sunday — which was, by grim coincidence, the 30th anniversary of Kennedy's Chappaquiddick accident — three priests said Mass for the family under the white tent that had been set up for Rory's wedding. A day later, Kennedy released a statement to the media whose opening sentence said it all: "We are filled with unspeakable grief and sadness by the loss of John and Carolyn, and of Lauren Bessette." He kept in constant contact with officials, checking on the progress of the search. At one point, to give family members a respite from their anguished vigil, he took several of them sailing on his boat, the Mya.

On Monday, he flew to Sagaponack, Long Island, to console Caroline, who had returned to her home there. Exactly 13 years earlier to the day, Kennedy had given Caroline away at her wedding. Since then, he had become such a jovial fixture in her family life that Caroline's 11-year-old daughter Rose drifted off to sleep each night clutching a stuffed animal she called Uncle Teddy.

It was less than two months since Caroline and Ted had been together for the annual Profiles in Courage dinner. Introducing him, Caroline had said of her uncle: "He has always been there for everyone who needs him."

Now he was there for her. He visited with Caroline's family for hours inside her brown-shingled two-story home. As the day wore on, sensing that the children needed a break, he brought Rose, 9-year-old Tatiana, and 6-year-old John outdoors for a spirited game of pickup basketball. It was a humid day, so the 67-year-old Kennedy played shirtless. His laughter punctuated the slap-slap-slap rhythm of the basketball as he called out the shots. Later, though, he spent an hour on the phone, checking on the search and recovery operation back on the Cape.

After he returned to Hyannis Port, the bad news was not long in coming. Late Tuesday night, a section of the plane's fuselage was discovered on the ocean floor seven miles off Martha's Vineyard, with John Jr.'s body still strapped inside. The bodies of Carolyn and Lauren lay nearby. Around noon on Wednesday, Kennedy and his two sons, Ted Jr. and Patrick, were transported near the site where the bodies had been found. At 4:30 p.m., the bodies of John Jr., Carolyn, and Lauren were brought to the surface. Kennedy helped identify John's body.

One day later, Kennedy led the funeral party as it left the family compound and boarded a Navy destroyer for a private ceremony. Family members cast John's ashes, and those of Carolyn and Lauren, into the ocean.

Delivering the eulogy for his nephew the next day at the memorial service, as he had for his own brother Bobby and for his mother, Rose, Kennedy fondly recalled the time when JFK Jr. was asked what he would do if he were elected president. John had replied with a grin: "I guess the first thing is call up Uncle Teddy and gloat." Said his uncle: "I loved that. It was so like his father."

Kennedy's voice cracked when he ended his tribute to John by paraphrasing a poem by William Butler Yeats: "We dared to think, in that other Irish phrase, that this John Kennedy would live to comb gray hair, with his beloved Carolyn by his side. But like his father, he had every gift but length of years."

After Kennedy concluded his eulogy, Caroline rose from her pew and clasped him in a hug.

The last is now the leader

Kennedy, who turns 77 today, had never expected to become the custodian of his family's sorrows. But when that role was thrust upon him, he learned to submerge his own pain enough to provide strength and reassurance for the rest of the family. As for himself, friends say, he coped by making room in his memory for the good times as well as the bad.

"You try to live with the upside and the positive aspects of it, the happier aspects and the joyous aspects, and try to muffle down the other kinds of concerns and anxiety and the sadness of it, and know that you have no alternative but to continue on," Kennedy said less than a year after John Jr.'s death. "And so you do."

It underscored the evolution that surprised so many people who knew the Kennedys: Teddy, the baby of the family, who had grown into a man who could sometimes be dissolute and reckless, had become the steady, indispensable patriarch, the one the family turned to in good times and bad.

A similar evolution played out in Kennedy's public life. When he first ran for the Senate at age 30, he was seen as a callow opportunist riding his brother Jack's coattails. But nearly five decades later, at an age when most people were retired, he remained consumed by the ham-and-egg details of constituent service, enacting the ethos taught to him by his grandfather, Honey Fitz. He still wanted to be the man constituents called when they were in a pinch.

Kennedy seemed to know, deep down, that if his life were to be marked by a heroic quality, it was not to be the lit-by-lightning kind his martyred brothers had, but rather the day-to-day reliability that John Updike captured in paying tribute to another Boston legend named Ted, one of Kennedy's boyhood heroes: Theodore Samuel Williams.

"For me, Williams is the classic ballplayer of the game on a hot August weekday, before a small crowd, when the only thing at stake is the tissue-thin difference between a thing done well and a thing done ill," Updike wrote. "Baseball is a game of the long season, of relentless and gradual averaging-out."

So is politics. And in the long season of Ted Kennedy's political career, any averaging-out would have to take into account his indefatigable exertions on behalf of people in need, at those times when — to them and, in a way, to him too — everything was at stake.

As a new century dawned, that quality would be tested anew by two convulsive events: the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and the war in Iraq.

One transforming morning

Ted Kennedy stared at the television. "That can't be a mistake," he said grimly.

It was around 9 a.m. on Sept. 11, 2001. Kennedy was standing stock-still in his outer office. A television on the desk of his chief of staff, Mary Beth Cahill, was tuned to live coverage of a shocking event that had just occurred: the crash of a plane into the World Trade Center in New York City.

The magnitude of the crisis was not yet known, and he had an important guest to prepare for. First lady Laura Bush was slated to arrive. They had scheduled a meeting that morning in advance of her testimony before the Senate education committee.

Mrs. Bush walked into the office. She had heard about the plane, but, like Kennedy, did not yet know that a terrorist attack was under way. The two of them went into his private office and began to talk. Then the second plane hit. Cahill hastily scribbled a note and hurried into Kennedy's office. Kennedy told Mrs. Bush what had happened. The two of them hastened to the outer office and stood, their eyes glued to the TV coverage until Secret Service agents hustled Mrs. Bush away to a secure location.

Kennedy accompanied her until she was off the Capitol grounds, then turned back toward his office. There would be a lot of work to do in the days ahead.

A voice of solace, strength

When Cindy McGinty of Foxborough first heard the voice on the other end of the line, so instantly recognizable with its impossibly broad vowels, she wondered who had chosen the worst possible time to play a prank on her. That couldn't really be Ted Kennedy, could it?

It was Sept. 12, 2001. One day earlier, McGinty's 42-year-old husband, Mike, who was on the 99th floor of the North Tower in the World Trade Center, had been killed. Her two sons, aged 7 and 8, had lost their father. "I was totally grief-stricken, scared out of my mind," recalls McGinty.

But now Ted Kennedy — for it was indeed he — was telling her how sorry he was for her loss and was saying that if there was anything she needed she should contact his office. There was nothing rote about his words, she recalls; no sense that he was hurrying through a list.

Yet over the next few weeks, Kennedy called each of the 177 families in Massachusetts who lost loved ones in 9/11. One was Sally White, of Walpole, who describes herself as a "dyed-in-the-wool conservative Republican," and whose daughter, Susan Blair, died in the 9/11 attacks. The last person whose voice she expected to hear on her telephone was that of the quintessential liberal Democrat. "I had not heard from one local politician, one medium politician, or certainly any federal guy. Nothing," says White. "He was the first one to call and offer assistance, or even sympathy."

Kennedy framed his words to White in the most personal of terms: He told her that his family's experience of loss had acquainted him with pain, and he talked about the time he had spent with Caroline after John Jr. was killed. He asked the grieving mother what Susan had been like. "He talked to me like he was my next-door neighbor, my best friend," White says. "He had all the time in the world for me. I was just overwhelmed by a person of his stature reaching out to me."

Those phone calls were the beginning of a special relationship with the families. "He saw this from the very beginning as a huge moment in the country's history," Cahill says. "The fact that [two of] the planes took off from Boston: He insisted that this become a special task for the office. It became calls to the families on a daily basis."

Like Kennedy, the 9/11 families had experienced shattering personal losses in full public view. Like him, they had to grieve with the eyes of the world upon them. So while he tried to cut bureaucratic red tape for them, he also performed acts of personal kindness that were not written into the job description of United States senator.

A month after that initial phone call, McGinty received an invitation from Kennedy's office to come to Boston for a meeting at the Park Plaza Hotel. By that point, McGinty, like many other 9/11 relatives, was feeling outgunned in a bureaucratic battle. The agencies that were supposed to help them were drowning them in paperwork instead. Getting something as simple as a death certificate was a challenge. It was unclear what benefits they were eligible for, or how to apply.

McGinty walked into a conference room at the Park Plaza, and there sat scores of people just like her. It was the first time these 9/11 family members had had a chance to meet one another.

Kennedy knew the emotional value of such a meeting, but he had a pragmatic agenda as well. He was intent on connecting the families with agencies that could help them. Ranged around the room were representatives from the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, the Social Security Administration, the United Way, and other governmental agencies and nonprofit organizations.

McGinty drew a breath, got to her feet, and spoke bluntly. "You have no idea how hard this is for us," she said. "I know you want to help, but you're not being helpful . . . Every one of you wants something from me. But you're making it too hard." The other family members clapped. Kennedy looked startled. As he left the meeting, McGinty would later learn, he turned to an aide and said: "I don't want to ever hear that Mrs. McGinty or one of the other families has this problem. Fix it!"

He arranged for an advocate, whose task was to help with the paperwork and applications for assistance, to be available to each 9/11 family. He assigned two staffers to work for a full year on the needs of the group. On Capitol Hill, he helped push through legislation to provide healthcare and grief counseling benefits for the families. He urged Senate majority leader Tom Daschle to support the appointment of a former Kennedy chief of staff, Kenneth Feinberg, as the special master of the 9/11 Victims Compensation Fund.

But Kennedy remained a lifeline for the families in ways that were often not in public view.

One summer day in 2002, the phone rang in the McGinty home. It was a Kennedy staffer, who asked McGinty: "What are you doing this weekend? How would you like to go sailing with the senator?" That weekend, McGinty, her two sons, and three of her relatives sailed in the waters off Hyannis on the Mya, with Kennedy at the helm. He cracked jokes and told stories, putting the children at ease.

A year later, McGinty was seated near Kennedy at a 9/11 ceremony. He scribbled something on his program, then pushed it across the table to her. "How are your two little sailors doing?" the note read.

When Kennedy learned that Christie Coombs of Abington, whose husband, Jeff, was killed on 9/11, had set up a charitable foundation in her husband's name, he began sending her watercolors, painted and signed by him, for her to auction off. When he learned that Sally White was running a fund-raiser in Susan's name for special needs children, Kennedy sent her a signed painting he had done of the Mya.

As the anniversary of Sept. 11 neared each year, Kennedy made sure to send a letter to the families. To Coombs, he wrote on Sept. 11, 2005: "Dear Christie, Vicki and I wanted you to know that we are thinking of you and your entire family during this difficult time of year. As you know so well, the passage of time never really heals the tragic memory of such a great loss, but we carry on, because we have to, because our loved one would want us to, and because there is still light to guide us in the world from the love they gave us."

In those words — "we carry on, because we have to" — Coombs sees evidence that Kennedy's own losses have given him insight into hers. "It feels very personal," she says. "This just tells me that he knows. He gets it. And so few people do."

War's foe, soldiers' friend

From the beginning, Kennedy argued that the war in Iraq was a mistake. Convinced that President George W. Bush had not made the case that Iraq represented an imminent threat to the United States, Kennedy was one of only 23 senators to vote on Oct. 11, 2002, against the resolution granting Bush the authority to invade Iraq.

"The power to declare war is the most solemn responsibility given to Congress by the Constitution," Kennedy said on the Senate floor. "We must not delegate that responsibility to the president in advance."

Later, as the insurgency grew and many other senators were shielding their opposition in the name of supporting the troops, Kennedy declared Iraq to be "Bush's Vietnam."

In his view, he was supporting the troops — and he took a personal interest in soldiers from Massachusetts. By October 2003, more than a dozen Massachusetts troops had lost their lives in Iraq. Twenty-year-old John D. Hart of Bedford was the latest.

Kennedy called the grieving parents, Brian and Alma Hart, to ask whether he could attend John's burial. Brian said yes, adding that there was something about John's death he wanted to discuss with him. So on Nov. 4, an SUV pulled up inside Arlington National Cemetery and Kennedy emerged, accompanied by two aides. They and the Harts went into the office of the cemetery administrator for a private conversation. Kennedy, who often stopped by Arlington National Cemetery to visit the graves of his brothers, began with some personal advice. "The best time to visit Arlington is the morning," he said. "It's cooler, and the crowds aren't there yet."

Brian and Alma told the senator that John had been ambushed while riding in a canvas-topped Humvee that had no armor, no bulletproof shields, not even a metal door. And they told him that John had predicted that very scenario just a few days earlier, in an anxious phone call home. Brian told Kennedy how, since John's death, he had dug into the issue of armored vehicles, conducting research online and calling manufacturing plants. He told Kennedy his research indicated armored Humvees were not being manufactured at anywhere close to the necessary rate.

Kennedy's face tightened as he listened. He had already been tracking this issue. Of the Massachusetts soldiers killed in the first phase of the Iraq war, fully one-third had died in unarmored trucks or Humvees. Kennedy told the Harts that he would hold a hearing on the matter. Still, it was hard for them not to feel at least some skepticism about a politician's — any politician's — promise. "Do you think we'll ever hear from him?" Alma asked Brian as they walked to the gravesite.

Within two weeks, Kennedy was grilling the Army chief of staff and the acting secretary of the Army in a hearing on the shortages of armored Humvees and body armor. When the officials told him it would take two years to produce a sufficient supply of armored Humvees, Kennedy demanded to know whether manufacturing plants were running 24 hours a day.

Kennedy and Hart became a sort of Mr. Inside-Mr. Outside team, pressuring the Army to speed up its acquisition process for armored Humvees. In early 2004, the Army announced plans for a doubling, from 220 to 450 a month, of heavily armored Humvees. Kennedy cosponsored legislation to provide $213 million to ensure that every Humvee that rolled off an assembly line was adequately armored. On April 21, 2005, the legislation passed, 60-40.

On the wall of the Harts' dining room is a large, framed tally sheet recording that Senate roll-call vote. It bears an inscription: "To Brian & Alma, This one was for you and for John. We couldn't have done it without you. April 05."

It is signed "Ted Kennedy."

Into twilight, fire still burns

In the decades since his 1980 presidential race, Kennedy's national reputation had hardened. Respected by liberals, he was so detested by conservatives that the mere mention of his name helped rake in GOP fund-raising dollars. But as he entered his 70s with unflagging energy, his conservative foes began to concede that there was something admirable in fighting that relentlessly on behalf of the people and the principles he cared about. Liberals, meanwhile, began to show their appreciation to Kennedy for carrying the liberal standard through several conservative Republican administrations.

It was against that backdrop that Kennedy took the stage in January 2004 at a packed high school gymnasium in Davenport, Iowa. He was there on behalf of his Massachusetts colleague, Senator John Kerry, who faced an uphill battle in his bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, with the all-important Iowa caucus less than two weeks away. There was reason to doubt how much good a Kennedy appearance would do. After all, Iowa had soundly rejected him in 1980, choosing Jimmy Carter instead.

Kennedy didn't skirt that issue. With a grin on his face, he reminded the assembled Iowans: "You voted for my brother. You voted for my other brother. You didn't vote for me!" The crowd roared with laughter. Kennedy continued, bellowing: "But if you vote for John Kerry, I'll forgive you!"

Kennedy stumped repeatedly for Kerry, convincing many blue-collar and minority voters that Kerry should be their guy. Thanks in part to Kennedy, Kerry pulled off an upset in Iowa and eventually won the Democratic nomination.

When Kennedy finished his roof-raising speech that first night in Davenport, "Love Train," the 1973 hit by the soul group The O'Jays, began pumping in over the PA system. Kennedy began to dance, his massive bulk swaying from side to side. He looked over at Mary Beth Cahill and winked. He was having the time of his life.

'I will be there'

When news broke in May 2008 that Ted Kennedy had a malignant brain tumor, many 9/11 families saw an opportunity to give something back to a man who had given them so much.

To most, the news was almost unthinkable. Kennedy had been back on the national stage in force, conferring a timely endorsement on Barack Obama for president — a move that now seemed almost to be a passing of the torch: Jack's torch, Bobby's torch, and his own.

Coombs sent him an email urging him to keep his spirits up. Then she wrote about Kennedy's illness in the journal she keeps, addressing her thoughts, as always, to her late husband, Jeff.

When McGinty heard about Kennedy's illness, she felt as if she had been punched in the stomach. But she rallied and said to herself: "This cancer doesn't know what it's up against." She sent Kennedy several get-well cards, along with a book titled "Listening is an Act of Love."

But like many of his well-wishers, she had no idea whether Kennedy would be well enough to make it to Denver for the Democratic National Convention, an event all the more significant because Obama would become the first African-American presidential nominee, something that heartened the old civil rights warrior in Kennedy.

By all medical logic, he should not have been anywhere near the convention. It was less than three months since he had undergone brain surgery. His usual moon face was further bloated from antiseizure medication. His mane of white hair had been thinned by cancer treatments.

But there he stood, looking out at thousands of delegates, many waving blue signs with "KENNEDY" in white letters. Before Kennedy took the stage, several TV commentators had remarked on the strange absence of passion and a coherent message inside the Pepsi Center.

If there was anything Ted Kennedy knew how to deliver, it was a passionate message. "It is so wonderful to be here," he told the delegates, and gave a little laugh. "Nothing — nothing — is going to keep me away from this special gathering tonight."

Kennedy proceeded to give the convention a much-needed jolt of adrenaline. In a voice that was still capable of rhetorical thunder, he spoke urgently about what he called the cause of his life: universal healthcare. He promised that Obama would close the book on the old politics of race, gender, and group. And then he brought the house down with this declaration: "I pledge to you that I will be there, next January, on the floor of the United States Senate, when we begin to write the next great chapter of American progress."

He lumbered away from the podium to chants of "Teddy! Teddy!"

There, onstage, was Vicki, who had barely left his side in three months, along with his own children, Ted Jr., Patrick, and Kara, and his stepchildren, Curran and Caroline Raclin. There, too, were Caroline and several of the younger generation of Kennedys to whom he had been such an emotional bulwark.

In her Foxborough home, Cindy McGinty sat on her living room couch and watched, her eyes filled with tears. "There's just nothing that keeps that man down," she remembers thinking. She thought of all that Kennedy had done for her and countless others who were in need over the past half-century.

There had been a largeness to his flaws during that time. But there had been a largeness of spirit, too. As McGinty looked at the TV screen, she saw not a legend but a friend. "He's a real person," she says. "He's not just a picture in a history book."

For one thing, he knew the legislative battle was not over. "We'll be back to fight and fight and fight again," Kennedy vowed. But what really buoyed the senator's spirits was the prospect of the wedding that weekend of his niece, Rory, the youngest child of his brother Bobby, at the family compound in Hyannis Port. Rory had been born six months after her father was assassinated in June 1968 — a turning point in Ted Kennedy's life, the moment when, though only 36, he was thrust into the role of family patriarch.

The wedding promised to be the kind of family event that Kennedy absolutely reveled in, and as he walked down the Capitol steps, he talked animatedly about how much he was looking forward to it. He knew the compound would fill up with the two dozen nieces and nephews to whom he was affectionately known as "the Grand Fromage" — French for "the big cheese." He had been a surrogate dad through much of their youth, taking them on camping trips to the Berkshires, bringing them to Civil War battlefields, teaching them to sail, beaming up at them from the pew at their First Communions.

"He's more than an uncle to his nieces and nephews," says Caroline Kennedy, the daughter of President John F. Kennedy. "I just feel so lucky to have the connection to my father and my whole family history."

On those trips, Kennedy made sure to carve out time to take the youngsters, singly or in pairs, for walks in the woods or strolls on the beach. Though the ostensible purpose was to steep the children in an appreciation of history and nature, Kennedy was also intent on sending a message: We are an unbreakable unit.

"Those kids, he was the father to all of them," says Don Dowd, a friend who drove the clan on those outings. "They all relied on him: John's kids, and Bobby's, and his own."

But there was another, sadder duty for which the Kennedy family had come to rely on him. When there is a family crisis, notes Caroline, "He's the first person who calls, the first person who shows up." And it was that grim duty — rather than singing, dancing, and toasting at Rory's wedding — that Ted Kennedy would have to shoulder, once again, that summer weekend in 1999. And it was Caroline in particular who would need Kennedy's support.

On the night of Friday, July 16, setting in motion a drama that would rivet the nation and crack the heart of anyone old enough to remember a little boy's salute, a single-engine Piper Saratoga piloted by John F. Kennedy Jr. plunged into the ocean off Martha's Vineyard. It would be four days before the bodies of John Jr., 38, along with his wife, 33-year-old Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, and her 34-year-old sister, Lauren Bessette, would be found.

The senator had arrived in Hyannis Port earlier on Friday. A festive air surrounded the wedding preparations, with a large white tent on the lawn for the nearly 300 invited guests. Late that night, Kennedy was awakened with the news that John Jr.'s plane was overdue. Kennedy anxiously placed a call to John's apartment in the TriBeCa neighborhood of New York City. A friend who was staying in the apartment answered the phone. Kennedy asked him whether, perhaps, John's plane had not left. The friend told Kennedy that it had.

Around 2 a.m., a family friend telephoned the Coast Guard at Woods Hole to report a missing plane. By early morning, a rescue mission was in full swing and a heartsick Ted Kennedy had to step into a role with which he was all too familiar. Caroline was not there — she was on a rafting vacation in Idaho with her husband and three children — but the senator did his best to console other family members.

On Sunday — which was, by grim coincidence, the 30th anniversary of Kennedy's Chappaquiddick accident — three priests said Mass for the family under the white tent that had been set up for Rory's wedding. A day later, Kennedy released a statement to the media whose opening sentence said it all: "We are filled with unspeakable grief and sadness by the loss of John and Carolyn, and of Lauren Bessette." He kept in constant contact with officials, checking on the progress of the search. At one point, to give family members a respite from their anguished vigil, he took several of them sailing on his boat, the Mya.

On Monday, he flew to Sagaponack, Long Island, to console Caroline, who had returned to her home there. Exactly 13 years earlier to the day, Kennedy had given Caroline away at her wedding. Since then, he had become such a jovial fixture in her family life that Caroline's 11-year-old daughter Rose drifted off to sleep each night clutching a stuffed animal she called Uncle Teddy.

It was less than two months since Caroline and Ted had been together for the annual Profiles in Courage dinner. Introducing him, Caroline had said of her uncle: "He has always been there for everyone who needs him."

Now he was there for her. He visited with Caroline's family for hours inside her brown-shingled two-story home. As the day wore on, sensing that the children needed a break, he brought Rose, 9-year-old Tatiana, and 6-year-old John outdoors for a spirited game of pickup basketball. It was a humid day, so the 67-year-old Kennedy played shirtless. His laughter punctuated the slap-slap-slap rhythm of the basketball as he called out the shots. Later, though, he spent an hour on the phone, checking on the search and recovery operation back on the Cape.

After he returned to Hyannis Port, the bad news was not long in coming. Late Tuesday night, a section of the plane's fuselage was discovered on the ocean floor seven miles off Martha's Vineyard, with John Jr.'s body still strapped inside. The bodies of Carolyn and Lauren lay nearby. Around noon on Wednesday, Kennedy and his two sons, Ted Jr. and Patrick, were transported near the site where the bodies had been found. At 4:30 p.m., the bodies of John Jr., Carolyn, and Lauren were brought to the surface. Kennedy helped identify John's body.

One day later, Kennedy led the funeral party as it left the family compound and boarded a Navy destroyer for a private ceremony. Family members cast John's ashes, and those of Carolyn and Lauren, into the ocean.

Delivering the eulogy for his nephew the next day at the memorial service, as he had for his own brother Bobby and for his mother, Rose, Kennedy fondly recalled the time when JFK Jr. was asked what he would do if he were elected president. John had replied with a grin: "I guess the first thing is call up Uncle Teddy and gloat." Said his uncle: "I loved that. It was so like his father."

Kennedy's voice cracked when he ended his tribute to John by paraphrasing a poem by William Butler Yeats: "We dared to think, in that other Irish phrase, that this John Kennedy would live to comb gray hair, with his beloved Carolyn by his side. But like his father, he had every gift but length of years."

After Kennedy concluded his eulogy, Caroline rose from her pew and clasped him in a hug.

The last is now the leader

Kennedy, who turns 77 today, had never expected to become the custodian of his family's sorrows. But when that role was thrust upon him, he learned to submerge his own pain enough to provide strength and reassurance for the rest of the family. As for himself, friends say, he coped by making room in his memory for the good times as well as the bad.

"You try to live with the upside and the positive aspects of it, the happier aspects and the joyous aspects, and try to muffle down the other kinds of concerns and anxiety and the sadness of it, and know that you have no alternative but to continue on," Kennedy said less than a year after John Jr.'s death. "And so you do."

It underscored the evolution that surprised so many people who knew the Kennedys: Teddy, the baby of the family, who had grown into a man who could sometimes be dissolute and reckless, had become the steady, indispensable patriarch, the one the family turned to in good times and bad.

A similar evolution played out in Kennedy's public life. When he first ran for the Senate at age 30, he was seen as a callow opportunist riding his brother Jack's coattails. But nearly five decades later, at an age when most people were retired, he remained consumed by the ham-and-egg details of constituent service, enacting the ethos taught to him by his grandfather, Honey Fitz. He still wanted to be the man constituents called when they were in a pinch.

Kennedy seemed to know, deep down, that if his life were to be marked by a heroic quality, it was not to be the lit-by-lightning kind his martyred brothers had, but rather the day-to-day reliability that John Updike captured in paying tribute to another Boston legend named Ted, one of Kennedy's boyhood heroes: Theodore Samuel Williams.

"For me, Williams is the classic ballplayer of the game on a hot August weekday, before a small crowd, when the only thing at stake is the tissue-thin difference between a thing done well and a thing done ill," Updike wrote. "Baseball is a game of the long season, of relentless and gradual averaging-out."

So is politics. And in the long season of Ted Kennedy's political career, any averaging-out would have to take into account his indefatigable exertions on behalf of people in need, at those times when — to them and, in a way, to him too — everything was at stake.

As a new century dawned, that quality would be tested anew by two convulsive events: the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and the war in Iraq.

One transforming morning

Ted Kennedy stared at the television. "That can't be a mistake," he said grimly.

It was around 9 a.m. on Sept. 11, 2001. Kennedy was standing stock-still in his outer office. A television on the desk of his chief of staff, Mary Beth Cahill, was tuned to live coverage of a shocking event that had just occurred: the crash of a plane into the World Trade Center in New York City.

The magnitude of the crisis was not yet known, and he had an important guest to prepare for. First lady Laura Bush was slated to arrive. They had scheduled a meeting that morning in advance of her testimony before the Senate education committee.

Mrs. Bush walked into the office. She had heard about the plane, but, like Kennedy, did not yet know that a terrorist attack was under way. The two of them went into his private office and began to talk. Then the second plane hit. Cahill hastily scribbled a note and hurried into Kennedy's office. Kennedy told Mrs. Bush what had happened. The two of them hastened to the outer office and stood, their eyes glued to the TV coverage until Secret Service agents hustled Mrs. Bush away to a secure location.

Kennedy accompanied her until she was off the Capitol grounds, then turned back toward his office. There would be a lot of work to do in the days ahead.

A voice of solace, strength

When Cindy McGinty of Foxborough first heard the voice on the other end of the line, so instantly recognizable with its impossibly broad vowels, she wondered who had chosen the worst possible time to play a prank on her. That couldn't really be Ted Kennedy, could it?

It was Sept. 12, 2001. One day earlier, McGinty's 42-year-old husband, Mike, who was on the 99th floor of the North Tower in the World Trade Center, had been killed. Her two sons, aged 7 and 8, had lost their father. "I was totally grief-stricken, scared out of my mind," recalls McGinty.

But now Ted Kennedy — for it was indeed he — was telling her how sorry he was for her loss and was saying that if there was anything she needed she should contact his office. There was nothing rote about his words, she recalls; no sense that he was hurrying through a list.

Yet over the next few weeks, Kennedy called each of the 177 families in Massachusetts who lost loved ones in 9/11. One was Sally White, of Walpole, who describes herself as a "dyed-in-the-wool conservative Republican," and whose daughter, Susan Blair, died in the 9/11 attacks. The last person whose voice she expected to hear on her telephone was that of the quintessential liberal Democrat. "I had not heard from one local politician, one medium politician, or certainly any federal guy. Nothing," says White. "He was the first one to call and offer assistance, or even sympathy."

Kennedy framed his words to White in the most personal of terms: He told her that his family's experience of loss had acquainted him with pain, and he talked about the time he had spent with Caroline after John Jr. was killed. He asked the grieving mother what Susan had been like. "He talked to me like he was my next-door neighbor, my best friend," White says. "He had all the time in the world for me. I was just overwhelmed by a person of his stature reaching out to me."

Those phone calls were the beginning of a special relationship with the families. "He saw this from the very beginning as a huge moment in the country's history," Cahill says. "The fact that [two of] the planes took off from Boston: He insisted that this become a special task for the office. It became calls to the families on a daily basis."

Like Kennedy, the 9/11 families had experienced shattering personal losses in full public view. Like him, they had to grieve with the eyes of the world upon them. So while he tried to cut bureaucratic red tape for them, he also performed acts of personal kindness that were not written into the job description of United States senator.

A month after that initial phone call, McGinty received an invitation from Kennedy's office to come to Boston for a meeting at the Park Plaza Hotel. By that point, McGinty, like many other 9/11 relatives, was feeling outgunned in a bureaucratic battle. The agencies that were supposed to help them were drowning them in paperwork instead. Getting something as simple as a death certificate was a challenge. It was unclear what benefits they were eligible for, or how to apply.

McGinty walked into a conference room at the Park Plaza, and there sat scores of people just like her. It was the first time these 9/11 family members had had a chance to meet one another.

Kennedy knew the emotional value of such a meeting, but he had a pragmatic agenda as well. He was intent on connecting the families with agencies that could help them. Ranged around the room were representatives from the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, the Social Security Administration, the United Way, and other governmental agencies and nonprofit organizations.

McGinty drew a breath, got to her feet, and spoke bluntly. "You have no idea how hard this is for us," she said. "I know you want to help, but you're not being helpful . . . Every one of you wants something from me. But you're making it too hard." The other family members clapped. Kennedy looked startled. As he left the meeting, McGinty would later learn, he turned to an aide and said: "I don't want to ever hear that Mrs. McGinty or one of the other families has this problem. Fix it!"

He arranged for an advocate, whose task was to help with the paperwork and applications for assistance, to be available to each 9/11 family. He assigned two staffers to work for a full year on the needs of the group. On Capitol Hill, he helped push through legislation to provide healthcare and grief counseling benefits for the families. He urged Senate majority leader Tom Daschle to support the appointment of a former Kennedy chief of staff, Kenneth Feinberg, as the special master of the 9/11 Victims Compensation Fund.

But Kennedy remained a lifeline for the families in ways that were often not in public view.

One summer day in 2002, the phone rang in the McGinty home. It was a Kennedy staffer, who asked McGinty: "What are you doing this weekend? How would you like to go sailing with the senator?" That weekend, McGinty, her two sons, and three of her relatives sailed in the waters off Hyannis on the Mya, with Kennedy at the helm. He cracked jokes and told stories, putting the children at ease.

A year later, McGinty was seated near Kennedy at a 9/11 ceremony. He scribbled something on his program, then pushed it across the table to her. "How are your two little sailors doing?" the note read.

When Kennedy learned that Christie Coombs of Abington, whose husband, Jeff, was killed on 9/11, had set up a charitable foundation in her husband's name, he began sending her watercolors, painted and signed by him, for her to auction off. When he learned that Sally White was running a fund-raiser in Susan's name for special needs children, Kennedy sent her a signed painting he had done of the Mya.

As the anniversary of Sept. 11 neared each year, Kennedy made sure to send a letter to the families. To Coombs, he wrote on Sept. 11, 2005: "Dear Christie, Vicki and I wanted you to know that we are thinking of you and your entire family during this difficult time of year. As you know so well, the passage of time never really heals the tragic memory of such a great loss, but we carry on, because we have to, because our loved one would want us to, and because there is still light to guide us in the world from the love they gave us."

In those words — "we carry on, because we have to" — Coombs sees evidence that Kennedy's own losses have given him insight into hers. "It feels very personal," she says. "This just tells me that he knows. He gets it. And so few people do."

War's foe, soldiers' friend

From the beginning, Kennedy argued that the war in Iraq was a mistake. Convinced that President George W. Bush had not made the case that Iraq represented an imminent threat to the United States, Kennedy was one of only 23 senators to vote on Oct. 11, 2002, against the resolution granting Bush the authority to invade Iraq.

"The power to declare war is the most solemn responsibility given to Congress by the Constitution," Kennedy said on the Senate floor. "We must not delegate that responsibility to the president in advance."

Later, as the insurgency grew and many other senators were shielding their opposition in the name of supporting the troops, Kennedy declared Iraq to be "Bush's Vietnam."

In his view, he was supporting the troops — and he took a personal interest in soldiers from Massachusetts. By October 2003, more than a dozen Massachusetts troops had lost their lives in Iraq. Twenty-year-old John D. Hart of Bedford was the latest.

Kennedy called the grieving parents, Brian and Alma Hart, to ask whether he could attend John's burial. Brian said yes, adding that there was something about John's death he wanted to discuss with him. So on Nov. 4, an SUV pulled up inside Arlington National Cemetery and Kennedy emerged, accompanied by two aides. They and the Harts went into the office of the cemetery administrator for a private conversation. Kennedy, who often stopped by Arlington National Cemetery to visit the graves of his brothers, began with some personal advice. "The best time to visit Arlington is the morning," he said. "It's cooler, and the crowds aren't there yet."

Brian and Alma told the senator that John had been ambushed while riding in a canvas-topped Humvee that had no armor, no bulletproof shields, not even a metal door. And they told him that John had predicted that very scenario just a few days earlier, in an anxious phone call home. Brian told Kennedy how, since John's death, he had dug into the issue of armored vehicles, conducting research online and calling manufacturing plants. He told Kennedy his research indicated armored Humvees were not being manufactured at anywhere close to the necessary rate.

Kennedy's face tightened as he listened. He had already been tracking this issue. Of the Massachusetts soldiers killed in the first phase of the Iraq war, fully one-third had died in unarmored trucks or Humvees. Kennedy told the Harts that he would hold a hearing on the matter. Still, it was hard for them not to feel at least some skepticism about a politician's — any politician's — promise. "Do you think we'll ever hear from him?" Alma asked Brian as they walked to the gravesite.

Within two weeks, Kennedy was grilling the Army chief of staff and the acting secretary of the Army in a hearing on the shortages of armored Humvees and body armor. When the officials told him it would take two years to produce a sufficient supply of armored Humvees, Kennedy demanded to know whether manufacturing plants were running 24 hours a day.

Kennedy and Hart became a sort of Mr. Inside-Mr. Outside team, pressuring the Army to speed up its acquisition process for armored Humvees. In early 2004, the Army announced plans for a doubling, from 220 to 450 a month, of heavily armored Humvees. Kennedy cosponsored legislation to provide $213 million to ensure that every Humvee that rolled off an assembly line was adequately armored. On April 21, 2005, the legislation passed, 60-40.

On the wall of the Harts' dining room is a large, framed tally sheet recording that Senate roll-call vote. It bears an inscription: "To Brian & Alma, This one was for you and for John. We couldn't have done it without you. April 05."

It is signed "Ted Kennedy."

Into twilight, fire still burns

In the decades since his 1980 presidential race, Kennedy's national reputation had hardened. Respected by liberals, he was so detested by conservatives that the mere mention of his name helped rake in GOP fund-raising dollars. But as he entered his 70s with unflagging energy, his conservative foes began to concede that there was something admirable in fighting that relentlessly on behalf of the people and the principles he cared about. Liberals, meanwhile, began to show their appreciation to Kennedy for carrying the liberal standard through several conservative Republican administrations.

It was against that backdrop that Kennedy took the stage in January 2004 at a packed high school gymnasium in Davenport, Iowa. He was there on behalf of his Massachusetts colleague, Senator John Kerry, who faced an uphill battle in his bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, with the all-important Iowa caucus less than two weeks away. There was reason to doubt how much good a Kennedy appearance would do. After all, Iowa had soundly rejected him in 1980, choosing Jimmy Carter instead.

Kennedy didn't skirt that issue. With a grin on his face, he reminded the assembled Iowans: "You voted for my brother. You voted for my other brother. You didn't vote for me!" The crowd roared with laughter. Kennedy continued, bellowing: "But if you vote for John Kerry, I'll forgive you!"

Kennedy stumped repeatedly for Kerry, convincing many blue-collar and minority voters that Kerry should be their guy. Thanks in part to Kennedy, Kerry pulled off an upset in Iowa and eventually won the Democratic nomination.

When Kennedy finished his roof-raising speech that first night in Davenport, "Love Train," the 1973 hit by the soul group The O'Jays, began pumping in over the PA system. Kennedy began to dance, his massive bulk swaying from side to side. He looked over at Mary Beth Cahill and winked. He was having the time of his life.

'I will be there'

When news broke in May 2008 that Ted Kennedy had a malignant brain tumor, many 9/11 families saw an opportunity to give something back to a man who had given them so much.

To most, the news was almost unthinkable. Kennedy had been back on the national stage in force, conferring a timely endorsement on Barack Obama for president — a move that now seemed almost to be a passing of the torch: Jack's torch, Bobby's torch, and his own.

Coombs sent him an email urging him to keep his spirits up. Then she wrote about Kennedy's illness in the journal she keeps, addressing her thoughts, as always, to her late husband, Jeff.

When McGinty heard about Kennedy's illness, she felt as if she had been punched in the stomach. But she rallied and said to herself: "This cancer doesn't know what it's up against." She sent Kennedy several get-well cards, along with a book titled "Listening is an Act of Love."

But like many of his well-wishers, she had no idea whether Kennedy would be well enough to make it to Denver for the Democratic National Convention, an event all the more significant because Obama would become the first African-American presidential nominee, something that heartened the old civil rights warrior in Kennedy.

By all medical logic, he should not have been anywhere near the convention. It was less than three months since he had undergone brain surgery. His usual moon face was further bloated from antiseizure medication. His mane of white hair had been thinned by cancer treatments.

But there he stood, looking out at thousands of delegates, many waving blue signs with "KENNEDY" in white letters. Before Kennedy took the stage, several TV commentators had remarked on the strange absence of passion and a coherent message inside the Pepsi Center.

If there was anything Ted Kennedy knew how to deliver, it was a passionate message. "It is so wonderful to be here," he told the delegates, and gave a little laugh. "Nothing — nothing — is going to keep me away from this special gathering tonight."

Kennedy proceeded to give the convention a much-needed jolt of adrenaline. In a voice that was still capable of rhetorical thunder, he spoke urgently about what he called the cause of his life: universal healthcare. He promised that Obama would close the book on the old politics of race, gender, and group. And then he brought the house down with this declaration: "I pledge to you that I will be there, next January, on the floor of the United States Senate, when we begin to write the next great chapter of American progress."

He lumbered away from the podium to chants of "Teddy! Teddy!"

There, onstage, was Vicki, who had barely left his side in three months, along with his own children, Ted Jr., Patrick, and Kara, and his stepchildren, Curran and Caroline Raclin. There, too, were Caroline and several of the younger generation of Kennedys to whom he had been such an emotional bulwark.

In her Foxborough home, Cindy McGinty sat on her living room couch and watched, her eyes filled with tears. "There's just nothing that keeps that man down," she remembers thinking. She thought of all that Kennedy had done for her and countless others who were in need over the past half-century.

There had been a largeness to his flaws during that time. But there had been a largeness of spirit, too. As McGinty looked at the TV screen, she saw not a legend but a friend. "He's a real person," she says. "He's not just a picture in a history book."

Go to:

No comments:

Post a Comment